Maryam Azwer

7.Lessons Learned from Gender-Based Violence Reporting

Journalists from around the globe, who met at the consultations convened by the Center for Women’s Global leadership in 2018 and 2019, discussed the key lessons learned from their experience reporting on gender-based violence.

The journalists said that regardless of its prevalence and context, gender-based violence is preventable and should be portrayed as a violation of universally protected basic rights and freedoms.

Highlighted Lessons

- Securing relevant and reliable data may require:

- Seeking disaggregated data (broken down by gender, age, race, location, etc.)

- Questioning data trends: for instance, do they reflect changes in violence rates or in reporting trends among victims?

- Being aware of data gaps: what are official statistics not counting/measuring?

- Reporting on women’s perceptions of risks as well as actual incidents of violence

- Learning from expert sources: Academic experts, NGOs, advocates, and service providers can give invaluable context, story ideas, and guided access to survivors.

- Understanding that individual stories are more compelling when linked to patterns of harassment and violence, root causes, contributing factors and other forms of discrimination and abuse in the community.

- Contributing to the public discourse by exposing the multiple reasons why a majority of women may not report incidents of harassment or violence and exploring the lessons learned from the #MeToo movement.

- Focusing the narrative on key issues of prevention and accountability, regardless of the immediate circumstances leading to acts of violence (in the life of a perpetrator or a victim, for example) or increases in patterns of violence (such as during the COVID-19 pandemic).

- Following up on news stories broadens the public understanding of key issues such as:

- Implementation and impact of new laws and policies addressing gender-based violence

- Accountability of perpetrators and government agencies

- Long lasting impact of violence on the dignity, health, and livelihood of survivors

- Community-based solutions

- Featuring traditionally underreported or unreported issues, such as the disproportionate and multi-layered impact of gender-based violence on the most vulnerable: girls, migrants, Indigenous communities, LGBT people, informal sector workers, migrants, and disabled women, among others.

7.7.1.Femicide

7.7.1.1.The concept of femicide

The term “femicide,” although coined in the 19th century, was popularized in the ’70s by the late feminist sociologist Diana Russell. She defined it as “the killing of females by males because they are female … When the gender of the victim is irrelevant to the perpetrator, the murder qualifies as a non-femicidal crime.”1

Russell hoped that the term could become a tool to mobilize against this most extreme form of gender-based violence, but it took almost three decades for the concept to be disseminated. In 2004, she met a prominent Mexican politician and feminist scholar, Marcela Lagarde, who invited her to speak in Juarez, Mexico. Lagarde later chaired a commission on femicide in the Mexican congress. Freelance journalist and former Fulbright scholar Aaron Shulman credited Lagarde for the spread of her advocacy efforts to Guatemala where, he wrote in the Dec. 28, 2010, edition of The New Republic:2

“Activists, in dialogue with their Mexican counterparts, grew enthusiastic about using the term to combat murders in their own country, which had become a kind of Juarez writ large … Thus the idea of ‘femicide’ struck a chord. In 2008, prompted by a domestic campaign and international pressure, the Guatemalan congress passed Decree-22, the Law Against Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women.”

“The word [feminicidio] has certainly affected Guatemalan culture, becoming a part of the national lexicon and entering the speech of everyday people as well as sensationalist tabloids,” Shulman wrote. “And there has been a significant increase in reports of violence against women brought to the police. What’s more, the word has been a useful tool for people trying to roll back Guatemala’s culture of impunity, providing publicity and legitimacy to anti-femicide groups which have found it easier to send offenders to jail.”

Globally, no universal consensus has been reached on the definition of femicide/feminicide, but the term is increasingly used to include a wide variety of gender-related killings of women punishable under domestic laws. It is worth noting that not all languages having a precisely equivalent term; the scope of the concept may vary semantically and legally. At the international level, however, femicide has been recognized as the most extreme form of gender-based violence.3

The late Mexican journalist Sergio González Rodríguez, who investigated the Ciudad Juarez femicides, in the Mexican border state of Chihuahua, summarized the essence of the term:

“Men are not killed for being men. Women are killed for being women, and they are victims of masculine violence because they are women. It is a hate crime against the female gender. We cannot ignore this. These are crimes of power. Yes, men are killed like flies, but they are not killed for being men.”4

Similarly, after founding the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability, Myrna Dawson highlighted the misogynistic roots of femicide:

“Femicide is the misogynistic killing of women by men,” she said. “We need to label it as such to distinguish it from the killing of men – they too are most often killed by men, but for different reasons and in different situations … Until we label misogynistic killings for what they are, their underlying motivations will be obscured and our ability to respond disabled.”5

Until we label misogynistic killings for what they are, their underlying motivations will be obscured and our ability to respond disabled.

Government and intergovernmental entities, as well as academics, women’s rights advocates, and human rights law experts, have contributed different definitions of the word “femicide.” Following are several complementary definitions selected by CWGL to help journalists relay its complexity to their viewers and readers. This terminology is also directly related to issues of data collection, legal protection and remedies, accountability, and prevention.

SELECTED DEFINITIONS OF FEMICIDEDeclaration on Femicide (2008)

Article 2, adopted by the Committee of Experts of the Follow-up Mechanism to the Organization of American States Convention of Belém do Pará.

“Femicide is the violent death of women based on gender, whether it occurs within the family, a domestic partnership, or any other interpersonal relationship; in the community, by any person, or when it is perpetrated or tolerated by the state or its agents, by action or omission.”

Understanding and addressing violence against women (2012)World Health Organization

“Femicide is generally understood to involve intentional murder of women because they are women, but broader definitions include any killings of women or girls.

Femicide differs from male homicide in specific ways. For example, most cases of femicide are committed by partners or ex-partners, and involve ongoing abuse in the home, threats or intimidation, sexual violence or situations where women have less power or fewer resources than their partner.”

Modalities for the establishment of a femicide or gender-related killing watch, 2016

A thematic report by Dubravka Šimonović, UN Rapporteur on violence against women.

“Femicide, or the gender-related killing of women, is the killing of women because of their sex and/or gender … It is a clear violation of women’s rights, including the right to life, freedom from torture and to a life free from violence and discrimination.”

Those definitions encompass the main manifestations of femicide, initially categorized, in 2012, by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, Rashida Manjoo.6 Most categories were later adopted, among others, by the European Institute for Gender Equality7 and by the Latin American Model Protocol for the investigation of gender-related killings of women.8

Although designed specifically to guide the investigation and prosecution of these crimes, the protocol can also be very helpful to journalists reporting on them: It clearly identifies the different categories and types of femicide, their gender-related motives and root causes (especially in terms of intersectional discrimination), and the marginalized women most at risk.

MAIN CATEGORIES OF FEMICIDE

- Intimate partner femicide

- Killings of women and girls in the name of “honor”

- Targeted killings of women and girls in the context of armed conflict

- Dowry-related killings

- Killings of women and girls based on gender identity or sexual orientation

- Ethnic and indigenous identity-related killings

- Female infanticide and feticide9

- Deaths from harmful practices, such as female genital mutilation

- Deaths from neglect, starvation, or ill-treatment

- Targeted killings of women linked to human trafficking, drug dealing, small-arms proliferation, organized crime, and gang-related activities

7.7.1.2.Numbers matter

Journalists face a major challenge when it comes to accessing reliable data on femicide. Visual journalist Corinne Chin best formulated the issue in an article about the murder of women in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico:

“Femicide is not just the killing of victims who happen to be female. It’s a systematic violation of human rights. Whether through domestic violence or sexual assault, the victims of femicide are women who were killed because they are women. Because of this standard’s high burden of proof – and because so many women never have been found – official statistics are almost certainly unreliable.”10

Dubravka Šimonović, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, outlined new processes for the establishment of a femicide observatory in her September 2016 report to the UN General Assembly. The report stressed that “one of her immediate priorities is the prevention of femicide and the use of data on violence against women as a tool to that end … She proposed that data on the number of femicides, disaggregated by the age and ethnicity of victims, and indicating the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim, should be published annually.”11 The special rapporteur is still issuing an annual call for femicide-related data to encourage states to gather and publish updated statistics.12

In her 2016 report, the special rapporteur also gave several examples of data collection good practices that reporters may find useful to access statistics from their respective countries or use as comparative data.13

One such example of good practice is the Femicide Census Project, which collects data on femicide within the United Kingdom. It publishes annual statistics on the killings by men of women and girls over age 14 and, in addition to domestic violence cases, it includes a variety of sexually motivated attacks. The census, published in February 2020, reports on femicides in 2018.14

When the Femicide Census was launched in February 2015, Time magazine published an article headlined, “Someone is Finally Starting to Count Femicides.”15 National Correspondent Charlotte Alter took that opportunity to note that. "The U.S. does not track ‘femicide’ specifically, because we tend to call these murders ‘female homicides.’ And while there is a lot of research on fatal domestic violence, the data is not usually presented in the broader context of women being killed by men … Even if the U.S. is not quite on board with the phrasing yet, ‘femicide’ advocates say that the word is a useful way to think about these kinds of murders. Femicide includes any kind of murder where the victim’s gender is a factor in her death.”

That Time article illustrates the importance of linking terminology and data collection. A noteworthy attempt at documenting gender-related killings of women at the global level is the Global Study on Homicide published annually by the Vienna-based UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). In its 2019 report,16 the agency addresses the challenges of obtaining and compiling such data:

“The availability of data on intimate partner/family related homicide means that such killings of females are analysed in greater depth than other forms of ‘femicide’ and that the analysis focuses on how women and girls are affected by certain norms, harmful traditional practices and stereotypical gender roles. Although other forms of gender-related killing of women and girls are described, such as female infanticide and the killing of indigenous or aboriginal women, given severe limitations in terms of data availability, only literature-based evidence is provided.”

Examples of good journalistic practices

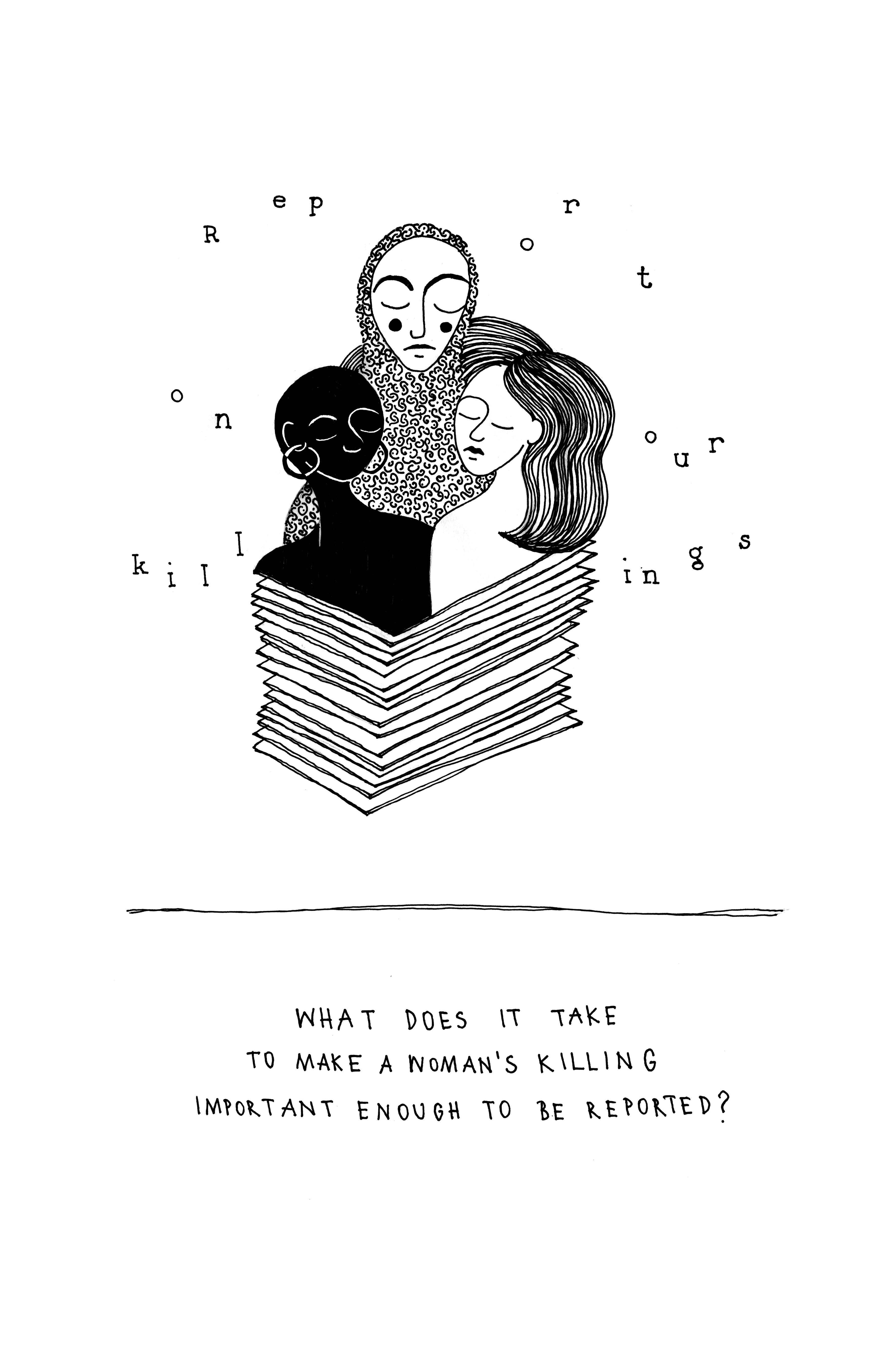

“The women killed on one day around the world”

As part of its annual “100 Women” feature, the BBC News website released, on Nov. 25, 2018, a very effective investigation of the global prevalence of femicide.17 The BBC chose the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women to report on its initiative. It had spent the previous month monitoring media reports of gender-related killings of women from a single day (chosen randomly), Oct. 1. Its reporters identified 47. This became an opportunity to combine personal stories behind the numbers with an examination of global trends based on UN statistics.

The next day, BBC Monitoring published a follow-up piece, “Violence against women: The stories behind the statistics,”18 detailing the research methods: “Despite our experience in media observation, this was not something that we – or, we believe anyone – had done before. It was not only about ensuring editorially robust data-gathering; it was about surfacing as many of the individual stories as we could find.” The piece ended with a key question: “It makes you wonder: What does it take to make a woman’s killing important enough to be reported?”

Illustrating another example of good practice, the reporting was immediately followed by helpful information and advice to women at risk of violence or abuse.

What does it take to make a woman’s killing important enough to be reported?

“#OneByOne: The murdered women in Pernambuco” (Brazil)

Launched in April 2018 by journalists working for the Jornal do Commercio de Comunicação media network, this documentation project (#UmaPorUma)18 told the stories of all women murdered in 2018 in the state of Pernambuco. The initiative, which involved 26 women journalists, led to the publication of a remarkable eight-page special edition on Feb. 3, 2019.

Aside from providing detailed statistics and analyses, the issue featured examples of best practices:

- Following-up: “The topic of femicide has always been in our daily lives. The feeling that each of us had is that we did daily coverage, but we did not follow up,” Julliana de Melo, one of the participating journalists, said.20

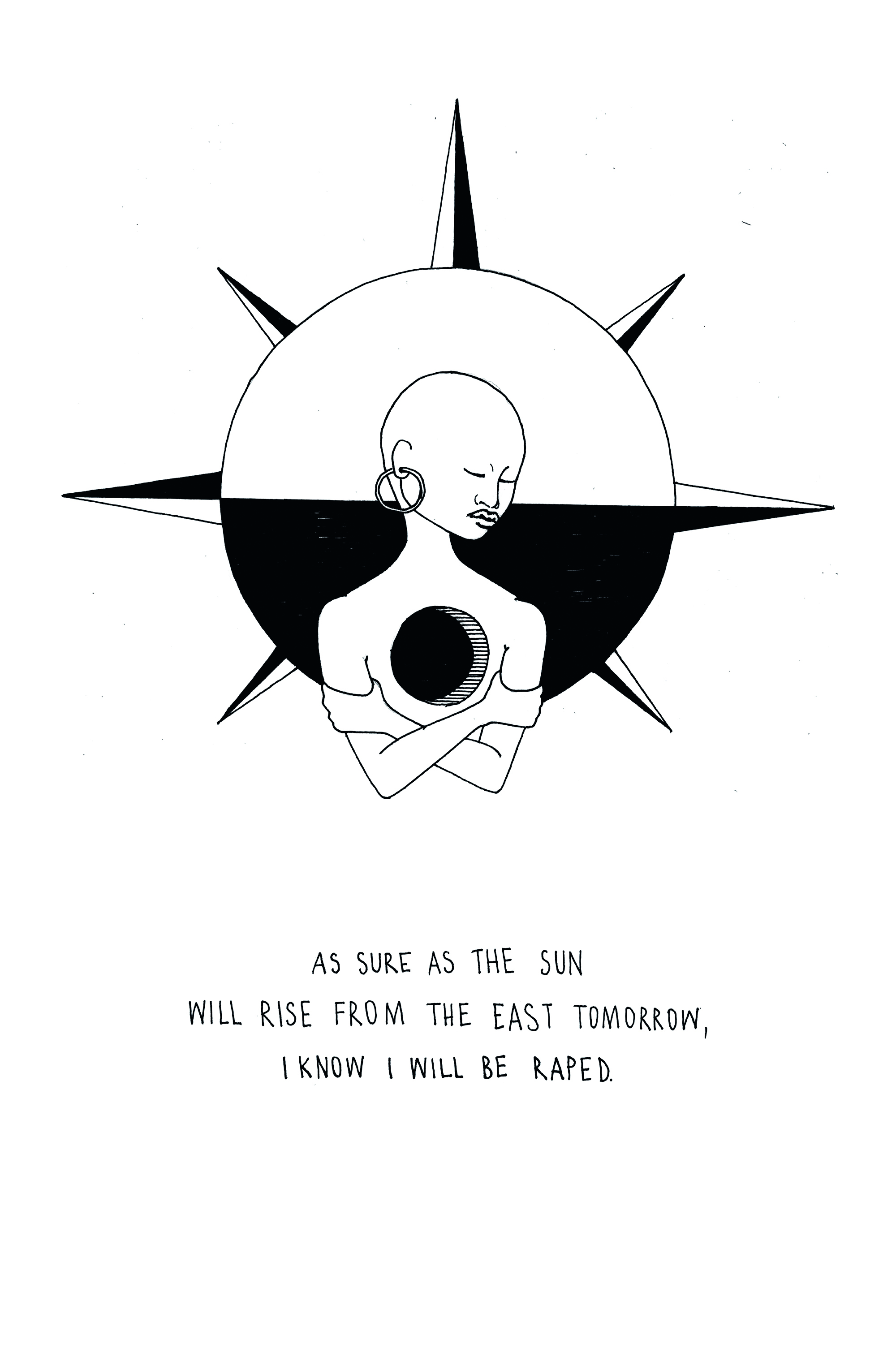

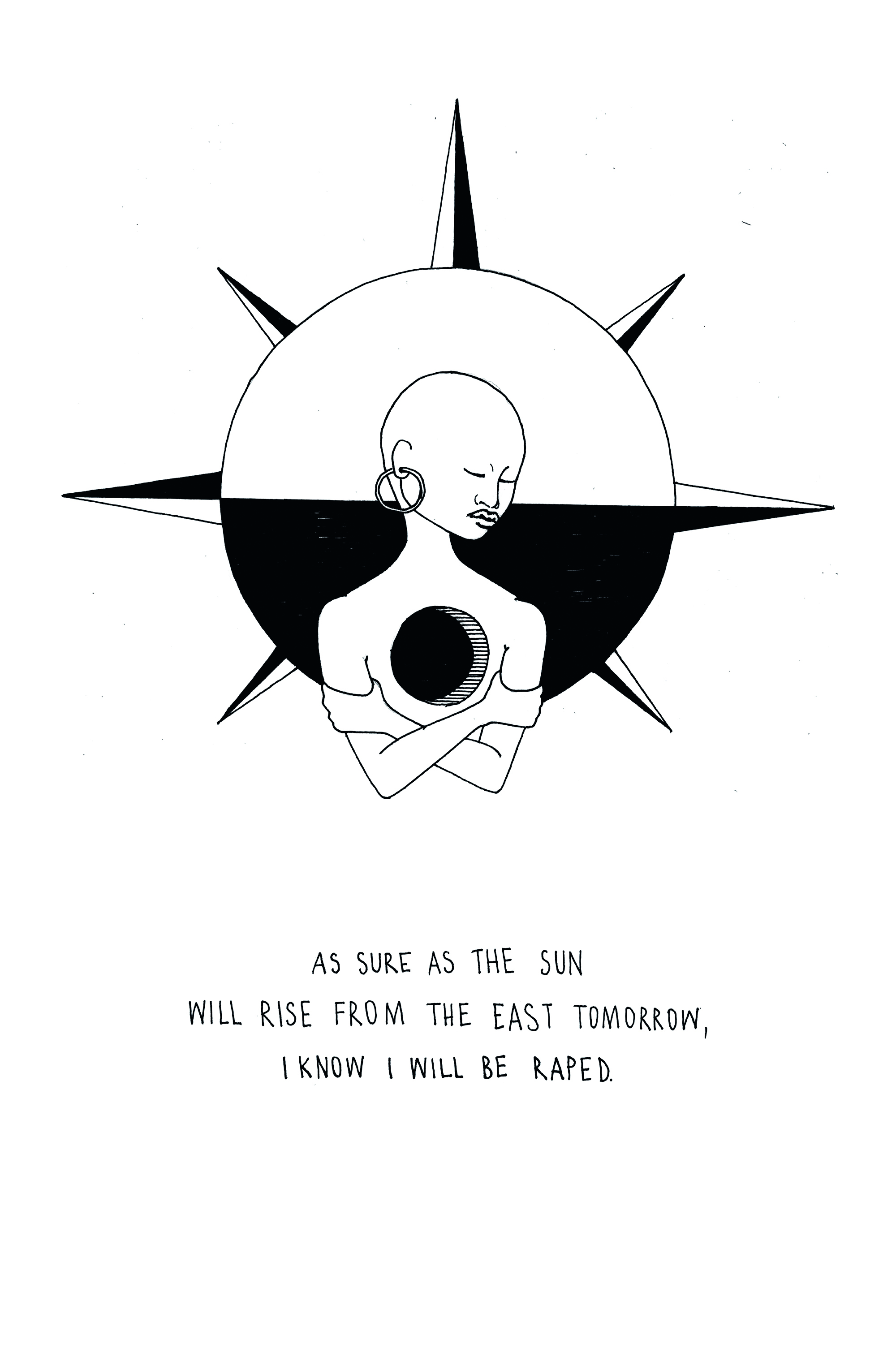

- Selecting pictures, illustrations and infographics that allow a non-sensationalizing portrayal of victims and fully respect their dignity.

“Voces Perdidas” (Lost Voices) in Mexico

In 2016, Mexican journalist and activist Frida Guerrera started documenting, investigating, and tallying every case of femicide in Mexico. First in a blog and in a Vice Mexico weekly column, and more recently on her remarkable website, vocesperdidas.mx, she tells the stories behind the statistics. At the same time, she exposes the impunity that fuels the normalization of gender-based violence, even in its most extreme forms. Guerrera pointed out on her website that out of the more than 3,000 cases of women murdered in Mexico in 2019, only 726 had been investigated as femicides.

“Not One Less”: An obituary for victims of femicide in Argentina

A comparable attempt to tell the stories behind the numbers was pursued by the largest newspaper in Argentina, Clarín. On June 3, 2020, it published a special obituary section featuring more than 300 women murdered in that country in the year prior to May 1, 2020.21 The date was chosen to mark the fifth anniversary of the protest movement Ni Una Menos (Not One Less) against the increasing number of femicides in Argentina and the region. The concept originated in Uruguay in 2019 when, as part of UN Women AD campaign “Gender obituaries”, the names of femicide victims were published in the daily funerals section of every newspaper.

The Clarín Group special section included the names of transgender victims of femicide, and showed the increased number of murders since the coronavirus pandemic began.

“Murder at Home” (Kenya)

“Murder at Home” is a Newsplex project exploring the impact of gender-based violence on Kenyan communities. Newsplex, the data journalism desk of the Nairobi-based Daily Nation, uses data analysis to inform public debate. Newsplex infographics and analysis, on Nov. 30, 2019, marked the Global 16 Days Campaign by highlighting the specific impact of gender-related killings.22

We also recommend to the media that it adopt codes of ethics to deal with cases of violence against women, especially femicides, promoting respect for the dignity and integrity of victims and avoiding the dissemination of morbid details and sexist or degrading stereotypes of women.

Earlier that year, scholar and trauma researcher Dr. Kathomi Gatwiri co-founded Counting Dead Women – Kenya, a Facebook page recording every woman’s murder reported in the Kenyan media. In an interview with the Christian Science Monitor she said: “This data is important because numbers don’t lie … These are numbers – and faces and stories – that you cannot argue with.”23 Conversely, her statistics are regularly used by the media to report on both the root causes and impact of femicides.

Such examples of journalistic good practices are consistent with the key recommendation made by the Committee of Experts on violence of the OAS Inter-American Commission of Women in their 2008 Declaration on Femicide:

“We also recommend to the media that it adopt codes of ethics to deal with cases of violence against women, especially femicides, promoting respect for the dignity and integrity of victims and avoiding the dissemination of morbid details and sexist or degrading stereotypes of women. The media should play a role in the ethical education of the citizenry, promote gender equity and equality and contribute to the eradication of violence against women.”24

María Sagrario González Flores mural (Mexico): “Every time I share my daughter’s story, I feel that she lives

on,” said Paula Flores, whose daughter María Sagrario González Flores disappeared on April 6, 1998. María Sagrario’s body was eventually discovered in an empty lot in Juárez, and it was clear she’d been raped and

murdered. Since then, Paula Flores has dedicated herself to preventing violence against women in the city. In

this photo, taken in 2016, she stands in front of her house where she had a muralist paint a portrait of Sagrario.

© Alice Driver

7.7.1.3.Learning from analyses of femicide media coverage

During the past decade, several scholars from the Americas working in the field of gender-based violence and criminal justice have made significant contributions to the analysis of the media coverage of femicide.

Lane Kirkland Gillespie (Boise State University, USA) and Tara Richards (University of Nebraska, USA) conducted a study25 based on a sample of 299 known cases of femicide (defined in this case as “the killing of a woman by a male intimate partner”). Those cases were mentioned in a total of 995 newspaper articles in the state of North Carolina (USA). This 2011 study “Exploring News Coverage of Femicide: Does Reporting the News Add Insult to Injury?” analyzed victim blaming, sources of information, and the use (or not) of an intimate partner violence (IPV) framework. The latter is especially important in terms of reporting best practices. The researchers sought an answer to the following question: “Did the articles portray the event as isolated or within the context of IPV as a social issue?” The study findings were summarized as follows:

“Articles that were framed as IPV [13.6%] were contextually different from those that were not. First, these articles included the perspective of domestic violence advocates, statistics on the prevalence of intimate partner abuse, and resources for victims and their families. Second, articles framed as IPV frequently placed blame for the femicide on inadequate response by the criminal justice system or faulty criminal justice practices.”

A 2013 Canadian study authored by Myrna Dawson (as Director of Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability) and Jordan Fairbairn,26 and based on the analysis of intimate partner homicide in three Toronto newspapers, revealed some similar findings:

“Results suggest that, in more recent years [1998-2002], news coverage is more likely to report a previous history of intimate partner violence and less likely to employ news that excuses or justifies the perpetrator’s actions. However, coverage continues to employ victim-blaming news frames and to portray intimate partner homicide as an individual event, in part, through the absence of the voices of violence against women organizations, researchers, and service providers as legitimate authorities.”

Chilean legal scholar Patsili Toledo and Chilean journalist and academic Claudia Lagos, referring to the work of Gillespie and Richards, published another study on “The Media and Gender-Based Murders of Women.”27 Theirs was commissioned by the Heinrich Boll Foundation and examines cases from Europe and Latin America.

According to Toledo and Lagos, the media frames, including the police and victim-blaming frames, “maintain a critical disconnection between femicides, presented as isolated, individual cases, and domestic violence as a broader social problem.”

The following case studies, from journalists based in Mexico and Honduras respectively, illustrate some of the issues raised by those researchers.

A. What’s love got to do with it? When femicide is framed as a crime of passion

Handbook Contributor Alice Driver is a Mexico City-based independent journalist and the author of 'More or Less Dead.'

BY ALICE DRIVER, MARCH 2020

“Cupid’s to Blame,” read the headline in ¡Pásala!, a Mexico City newspaper. The article included a graphic photo of Ingrid Escamilla, 25, who had been stabbed, skinned and disemboweled by her boyfriend. He had immediately confessed to everything. Escamilla was murdered on Feb. 8, 2020, in Mexico City. ¡Pásala!, one of the first newspapers to publish the story, framed it as a crime of passion and in addition to showing the mutilated body of the femicide victim with the story, a picture of her remains was also published on its front page, alongside a photo of a woman in a bikini. ¡Pásala! is far from the only media outlet to have framed femicide as a crime of passion and the proliferation of graphic photos of femicide victims in the Mexican media has been an issue for the past two decades. Feminists have long argued that publishing graphic photos of victims, especially without the permission of their families, re-victimizes the women.

In Escamilla’s case, police who arrived at the scene made the decision to film the perpetrator, Erick Francisco, 46. He was shirtless and covered in blood. They allowed him to explain that he had killed his girlfriend because she had threatened to kill him first. And then the police leaked the video to the press, which allowed the perpetrator of the crime to control the discourse surrounding the femicide victim.

In researching my book, More or Less Dead,28 which is about femicide in Mexico, I discovered that in many cases, misogyny of the police and other officials involved in investigating the crimes – ranging from comments speculating that the victim was a prostitute to telling journalists that femicide was a crime of passion – played a central role in how the violence was later covered in the media. Police also leaked photos of Escamilla’s mutilated remains to the media. The images sent shockwaves through the country and led to massive public protests about the levels of violence against women and the way victims of feminicide are re-victimized by the media.

To change the way femicide is represented in the media in Mexico and around the globe requires a discussion, such as the one that appeared in bajopalabra.com, about the ethics of how femicide victims are represented in print and photography. The prevailing coverage tends to focus on the physical violence and on describing it as gruesomely as possible, while showing shocking, graphic photos. That kind of coverage reads like trauma porn and, although some argue that people need to be shocked in order to pay attention, the problem is that no level of violence against women – not even what Escamilla experienced – is shocking enough. The issue at the heart of how femicide is covered in the media is that violence against women sells, particularly when it is represented in a sensational way. As journalists, we need to think about how we can represent the lives of victims with respect and to question police or other officials who frame such violence in misogynistic terms. Nobody, especially not perpetrators of femicide, should be provided with a media platform to justify violence against women.

In response to the publication of photos of Escamilla’s body, feminist groups around Mexico encouraged citizens to upload pictures of beautiful landscapes to social media with the hashtag #JusticeForIngrid in Spanish. They did it to counter the fact that one of the top searches on social media and on Google related to Escamilla was for photos of “Ingrid Escamilla body skinned.” Their efforts ensured that such searches would be overwhelmed by the photos that feminists and other citizens had posted.

Feminists, via coordinated protests around Mexico, have forced the media to recognize the prevalence of sexist, victim-blaming discourse around femicide. In a period of a few weeks, feminists had called for the creation of Ingrid’s Law, which was later proposed by Ernestina Godoy, the attorney general for justice in Mexico City. The law, if passed, would sanction public servants who leak images from open police investigations.

At a protest against femicide organized in Mexico City on Feb. 14, 2020, feminists chanted “our bodies are not a show” and held protest signs that read, in Spanish, “We demand responsible journalism that doesn’t revictimize us.” The protests forced the media to listen to and interview women and thus begin to discuss the ethics of how femicide victims have been represented. In the long run, it is women – many of them having been victims of violence – who will put their bodies in the streets and fearlessly voice their concerns to change the way femicide victims are represented in the media.

B. Media violence against Honduran women

Wendy Funes is an independent investigative journalist based in Honduras. This case study was adapted from an article published by “Reporteros de Investigación” in February 2018.29

THE ADAPTATION WAS TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY MARILSE RODRÍGUEZ GARCÍA

A study of the messaging that two daily newspapers in Tegucigalpa conveyed in 2016 reports about crimes against women’s lives finds that they constructed a narrative that justified their deaths by reinforcing gender roles, labeling, stigmatizing and revictimizing the primary victims/survivors, as well as the secondary victims (family members/community). The newspapers’ coverage demonstrated media violence. It was built on a similar construct of gender in both newspapers, which represented the events without proper investigation, basing the news on anonymous sources that, in most instances, transmitted messages from a faceless official voice.

Another principle from which the media violence sprang was the very similar structure in both newspapers, with active voice for the aggressors and the police, and passive voice for the women, their family members, and survivors. Because of the use of this language, the aggressors seemed to be active, while the victims were always stereotyped as passive.

Victims and their families, revictimized, also suffered symbolic violence from the media exposure of the bodies through graphic language, as evidence that a man exercised power over their bodies and "ended their lives."

My preliminary study analyzed 12 news articles of crimes against women’s lives within the context of violence against women. It was conducted through a critical analysis of the narratives. The articles from news reports were selected randomly for the study as a proposed first approach to the analysis of discourse in media criminology.

The lack of objectivity in the articles is a result of basing most of the information on anonymous official sources, without contrast, without a survivor's voice, people who witnessed the events, secondary victims (family), or professionals on matters of security, criminology, sociology, anthropology, or psychiatry. This latter group could help understand the reality of criminal phenomena as part of a social totality with different explanations and diverse solutions.

The newspapers focused their attention on the police-penal optics and limited death to criminal violence, without exploring social and structural violence promoted by the culture of war and death as a "means for peace." This in turn reinforces the symbolic violence and expressive violence that, according to feminist anthropologist Rita Laura Segato, serve to send a message of control and power from the victimizer, while in the coverage there is a kind of normalization or banalization of the violence.

The news was constructed with poor language, word redundancy, excessive use of pronouns in sentences, passive voice, ambiguous paragraphs, and imprecise data. "It would have been jealousy." The use of the verb "to be" in the conditional represents a sense of anteriority or refers to hypothetical actions. It serves to mitigate the reporter's responsibility in the newsroom. In this context, the conditional mode suggests a lack of commitment to reliability and validity, that is, it implies doubt as to the information.

"She was a graceful woman who liked to show her figure on Facebook; she liked to post photos to her Facebook page modeling her body, receiving hundreds of 'likes' every time she posted an image of her figure," quotes one purported news report, without specifying a source and without exploring the personality of the victim to explain the reason for that journalistic conclusion.

The newspapers' message was based on describing the motivation for each act; that is, media attention was focused on the criminal signature, rather than on the modus operandi, which might help solve the crime. Anonymous police officers offered their narratives at the scene, revictimizing the women without first investigating the possibility that the scenes of women’s violent deaths may have been altered, given complaints about police corruption.

In the analysis, the photographs communicated: doubts about the behavior of the victim; commiseration; doubts about sexual freedom and the victims’ showing off of their bodies in social media; anguish of family members; police as the only responsible authority; loneliness in tragedy; death as a mechanism of distraction and spectacle to satisfy the curiosity of the groups of inquisitive people who hang around the scene of a crime and, at the same time, the help and solidarity that ensue from the incident.

The news in both newspapers obscures the entire set of aggressors' behaviors and focuses only on the criminal behavior directed against the life of the female victims. It leaves out of the scene the subjugated people who obey and keep the victims helpless. While a man who was driving "was forced to,” it is said of the woman that "she was removed." The use of that verb objectifies her, and she ceases to be an animate subject, becoming an inanimate one. The representation is based on the defects of the aggressors, without specifying the emotions or virtues of each character.

What does it take to make a woman’s killing important enough to be reported?

7.7.1.4.“That’s not how it was. You need to get this right.”

A woman whose sister was murdered in an incident of domestic violence was quoted as saying: “After having read certain reports, I imagined my sister shouting: ‘No, no, that’s not how it was. You need to get this right.’”

That quotation is included in a 2018 publication of the London-based feminist organization Level Up: Dignity for dead women: Media guidelines for reporting domestic violence deaths.30 Level Up’s advocacy work to end sexism in the United Kingdom led it to create these guidelines to “set a bar for journalistic standards on fatal domestic abuse stories and help put an end to families of victims having their grief and trauma compounded by irresponsible reporting.” Its initial guidelines, after input from UK journalists (including from the BB C and the Huffpost), were adopted by the UK’s two main press regulators: The Independent Press Standards Organization (IPSO) and Impress. The guidelines can be accessed through the “External resources for journalists” section of the IPSO website.

Every article on fatal domestic abuse is an opportunity to help prevent future deaths.

In its introduction, Level Up asks journalists: “Before you write about fatal domestic abuse, understand that:

- “When someone has been killed by their partner or ex-partner, this is usually the endpoint to a sustained period of coercive control – not an isolated incident. Including the broader context is a matter of accuracy.

- “Research shows that narratives of ‘romantic love’ in domestic abuse deaths can lead to lighter sentencing in court.

- “Insensitive reporting has lasting traumatic impacts on victims’ families. Cultural and religious insensitivity detracts focus from the woman’s life that has been lost.

- “Every article on fatal domestic abuse is an opportunity to help prevent future deaths.”

Vox senior reporter Anna North recommends those guidelines in an excellent analysis of victim-blaming patterns in the media coverage of some types of femicide. Her Nov. 21, 2019, article features the case of Grace Millane, a British woman who was fatally strangled in New Zealand. Her “accidental’ death was attributed by the perpetrator and his defense lawyers to her “sexual fetishes”, which were also the focus of the media coverage of his trial. North concluded: “As the prosecutor pointed out, ‘you can’t consent to your own murder.’ “

You can’t consent to your own murder.

“It is reasonable for media outlets to cover the defense’s strategy”, North added in her Vox article, “but the way they cover it matters … Many media outlets were leading with the defense’s argument without giving equal prominence to the prosecution. While the attention to the [victim’s] sexual past may reflect a cultural tendency toward victim-blaming, it is also a strategy by media outlets to drive clicks by focusing on sex.”31

7.7.1.5.Selected global and domestic data resources

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

Since her 2015 call for all states to establish a femicide watch and publish disaggregated data on femicide, the UN Special Rapporteur has issued annual calls for states’ submissions and provided links to the reports from each responding country.

https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Women/SRWomen/Pages/CallForFemi- nicide2019.aspx

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

The first UNODC “Global Study on Homicide” was published in 2011. At the time of writing, the most recent study was dated July 2019. Booklet 5 of the report covers “Gender-related killings of women and girls” (68 pages):

The appended table provides useful information about which offenses are counted as “femicide” in the 18 countries (all in Latin America) that include a legal definition of such offenses in their respective criminal codes.

https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet_5.pdf

Fem[in]icide Watch

This global platform, launched in 2017, is a joint project of the United Nations Studies Association (UNSA) Global Network and UNSA Vienna

Academic Council of the United Nations System (May 2017)

“Establishing a Femicide Watch in Every Country” (Femicide publication, Volume VII, May 2017)

Small Arms Survey Research Notes

“A Gendered Analysis of Violent Deaths” (November 2016)

http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/H-Research_Notes/SAS- Research-Note-63.pdf

Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability

Its website features a comprehensive review of all the different types of femicide, as well as a library which includes global and regional resources.

http://femicideincanada.ca/library

It starts With us

“Honors the lives of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans, and two-spirits” and provides information about Canadian community databases documenting their murders.

http://itstartswithus-mmiw.com/

Violence Policy Center (USA)

“When Men Murder Women” (September 2020)

https://vpc.org/studies/wmmw2020.pdf

Women Count USA

A femicide accountability project (includes a database)

https://womencountusa.org/about

Observatorio de feminicidios (Argentina)

The Argentine Ministry of Security established the Observatory in 2016.

http://www.dpn.gob.ar/documentos/Observatorio_Femicidios_-_Femicide_ Report_2017_-_SSEC_OFDPN.pdf

Observatorio Feminicidios Colombia

https://observatoriofeminicidioscolombia.org/

National Citizen Observatory on Memicide (Mexico)

Observatorio Ciudadano Nacional del Feminicidio (OCNF). This is the largest femicide watch/observatory in Latin America.

https://www.observatoriofeminicidiomexico.org/

European Observatory on Femicide (EOF)

EOF is a network of country research groups in Europe and Israel.

http://eof.cut.ac.cy/about-eof/

Trans Murder Monitoring

This is a global monitoring project (started in 2009) of Berlin-based Transgender Europe.

https://transrespect.org/en/trans-murder-monitoring/

Féminicides par compagnons ou ex (France)

This volunteer collective has been documenting since 2016 murders by current or ex-partners reported in the French press or through social media. A major 2019 Agence France Presse investigation was based on their data.

7.7.1.6.Endnotes

Endnotes on chapter VII.I.

- Russell, D. (2011). The origin and importance of the term femicide. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from author’s website: https://www.dianarussell.com/origin_of_femicide.html

- Shulman A. (2010, December 28). The Rise of Femicide. The New Republic. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://newrepublic.com/article/80556/femicide-guatemala-decree-22

- United Nations, General Assembly, Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women (Section IV, Thematic focus: Modalities for the establishment of femicide or gender-related killings watch, par. 25), A/71/398 (23 September, 2016). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://undocs.org/en/A/71/398

- Quoted in: Driver, A. (2012, April 12). The femicide debate. Women’s Media Center. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.womensmediacenter.com/news-features/the-feminicide-debate

- Dawson, M. (2018, April 27). Why misogynistic killings need a public label. Policy Options. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2018/misogynistic-killings-need-public-label/

- United Nations, Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women ( Section III: Gender-related killings of women), A/HRC/20/16 (23 May 2012). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://undocs.org/A/HRC/20/16

- https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1128

- UN Women (2014). Latin American Model Protocol for the investigation of gender-related killings of women (par. 44–45). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020 from https://lac.unwomen.org/en/digiteca/publicaciones/2014/10/modelo-de-protocolo

- These sex-selective practices resulting in death are sometimes classified under the term “gen- dercide,” which the European Parliament defines as the “systematic, deliberate and gender-based mass killing of people belonging to a particular sex, with lethal consequences” in an October 2013 Resolution: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7- TA-2013-0400+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN

See also: McRobie, H. (2008, July 30). Recogniz- ing ‘gendercide’. The Guardian. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.theguardian. com/commentisfree/2008/jul/30/gender. warcrimes - Chin, C. & Schultz, E. (2020, March 8). Disappearing Daughters. The Seattle Times. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://projects.seattletimes.com/2020/femicide-juarez-mexico-border/

- United Nations, General Assembly, Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women (Section IV: Thematic focus: modalities for the establishment of femicide or gender-related killings watch, par. 29), A/71/398 (23 September, 2016). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://undocs.org/en/A/71/398

- https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Women/SRWomen/Pages/FemicideWatchCall2020.aspx

- United Nations, General Assembly, Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women (Section IV.C: Good practices on femicides and data collection), A/71/398 (23 September, 2016). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://undocs.org/en/A/71/398

- Femicide Census (2020). Annual report on UK femicides 2018. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://femicidescensus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Femicide-Census-Report-on-2018-Femicides-.pdf

- Alter, C. (2015, February 28). Someone is finally starting to count ‘femicides’. Time magazine. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://time.com/3670126/femicides-turkey-women-murders/

- UNODC (2019). Global Study on Homicide: Gender-related killing of women and girls (p.7). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet_5.pdf

- BBC News (2018, 25 November). The Women killed on one day around the world. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2019 from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-46292919

- Skippage, R. ( 2018, November 26). Violence against women: The story behind the statistics. BBC News. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-46307051

- http://produtos.ne10.uol.com.br/umaporuma/e-da-conta-de-todos-nos.php

- De Assis, C. (2018, May 16). Brazilian journalists launch project #OneByOne to tell the stories of murdered women in Pernambuco. Journalism in the Americas Blog, Knight Center at the University of Texas, Austin. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://latamjournalismreview.org/articles/brazilian-journalists-launch-project-onebyone-to-tell-the-stories-of-murdered-women-in-pernambuco/

- Clarín (2020, June 3). En el aniversario de Ni Una Menos, la Iniciativa Spotlight y Clarín publican los obituarios de las víctimas de femicidios del último año en Argentina. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.clarin.com/sociedad/aniversario-iniciativa-spotlight-clarin-publican-obituarios-victimas-femicidios-ultimo-ano-argentina_0_z_J-ijWuU.html

- Newsplex Team (2019, November 30). “Gender-based violence can break a woman.” Nation Newsplex. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.nation.co.ke/kenya/newsplex/gender-based-violence-can-break-a-woman-227928

- Brown, R.L. (2020, January 8). ‘Numbers don’t lie’: The team ‘Counting Dead Women’ in Kenya. Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved on September 30, 2020 from https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2020/0108/Numbers-don-t-lie-The-team-Counting-Dead-Women-in-Kenya

- Committee of Experts of the Follow-up Mechanism to the Belém do Pará Convention (MESECVI). Declaration on Femicide (2008, August 15). https://www.oas.org/en/mesecvi/docs/DeclaracionFemicidio-EN.pdf

- Richards, T.N., Gillespie L., & Smith, M.D. (2011, June 23). Exploring news coverage of femicide: Does reporting the news add insult to injury? Feminist Criminology, 6(3) 178-202. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.968.1776&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Fairbairn J., Dawson M. (2013). Canadian news coverage of intimate partner homicide: Analyzing changes over time. Feminist Criminology (Volume 8, Issue 3, pp. 147-176). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1557085113480824

- Toledo, P. & Lagos, C. (2014). The media and gender-based murders of women: Notes on the cases in Europe and Latin America. Commissioned and published by the Heinrich Boll Foundation. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://eu.boell.org/en/2014/07/24/media-and-gender-based-murders-women-notes-cases-europe-and-latin-america

- Driver, A.(2015). More or less dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the ethics of representation in Mexico. Tucson, USA: The University of Arizona Press.

- https://www.reporterosdeinvestigacion.com/2018/02/07/violencia-mediatica-en-los-delitos-contra-la-vida-de-mujeres-hondurenas/

- Starling, J. (2018). Dignity for dead women: Media guidelines for reporting domestic violence deaths. Level Up (UK). Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020 from https://www.welevelup.org/media-guidelines

- North, A. (2019, November 21). “She was fatally strangled. The media is making it about her sex life. Vox. Retrieved on Sept. 30, 2020, from https://www.vox.com/2019/11/21/20976064/grace-millane-death-new-zealand

Bonita Meyersfeld

7.7.2.Domestic Violence

7.7.2.1.Terminology

In English, several terms are used interchangeably: domestic violence or abuse, family violence, and intimate partner violence. Domestic violence is the term chosen in this handbook to reflect the lack of cross-cultural consensus on what defines a family structure. As early as 1996, the first UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, Radhika Coomaraswamy, recognized that “discussions on family violence have failed to include the broad range of women’s experiences with violence perpetrated against them by their intimates when that violence falls outside the narrow confines of the traditional family.”1 She defined domestic violence as “violence that occurs within the private sphere, generally between individuals who are related through intimacy, blood or law.”2

In a report to the UN General Assembly,3 the Special Rapporteur on torture, Nils Melzer, clarified in 2019 that “domestic violence includes a wide range of abusive conduct, from culpable neglect and abusive or coercive or excessively controlling behavior that aims to isolate, humiliate, intimidate or subordinate a person, to various forms of physical violence, sexual abuse and even murder. In terms of the intentionality, purposefulness and severity of the inflicted pain and suffering, domestic violence often falls nothing short of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” As such, it is considered a human rights violation that can lead, in its most extreme form, to femicide (see previous section).

Domestic violence often falls nothing short of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

As opposed to intimate partner violence, which refers to forms of abuse and controlling behaviors within an intimate relationship, domestic violence can also encompass abuse against a child or elder, and abuse by any member of a household, including domestic workers. Since the adoption of the Istanbul Convention4 in 2011, it can also include economic violence as a form of coercive control that deprives victims of their autonomy and dignity.

Domestic abuse is sometimes the preferred terminology to avoid limiting this form of violence to its physical manifestations.

“Using the term domestic abuse has spurred a discussion in Australia on the parts of abuse that go unnoticed, such as coercive control and systematic campaigns of domination and degradation” said Australian investigative journalist Jess Hill, who won the 2020 Stella Prize for her book on the topic.5

One in three women will experience physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in her life

7.7.2.2.Prevalence, causes, and risk factors

Selected statistics

The Progress of the World’s Women 2019–2020 report by UN Women6 includes a comprehensive source of statistics in its chapter titled “When home is where the harm is.” In particular, it provides new global and regional data on the “proportion of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15–49 subjected to physical or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months”. The world average is 18%, the highest proportion being 35% in Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand). According to UN Women,7 this global average represents 243 million women and girls.

The World’s Women 2020 Trends and Statistics report8, published at five-year intervals, features the latest available data for 112 countries during the period from 2005 to 2018. It was compiled by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). The countries with the highest proportion of violence were Afghanistan (46%), Equatorial Guinea (40%), and Vanuatu (33%). Other key findings are:

- 58% of countries have recorded a decrease in intimate partner violence since 2005

- Younger women (15–29 years) are at increased risk of experiencing IPV

- One in three women will experience physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in her life

Meanwhile, a 2013 WHO study9 estimates that “the global lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women aged 15–49 is 27%,” with the highest rate (51%) in Melanesia.

The global lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence among ever-partnered women [aged 15–69] is 30%.

In the United States, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (CDC 2018),10 “1 in 4 women experienced sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner and reported an IPV-related impact during their lifetime.”

Cautionary tales

Those sets of statistics illustrate the need to exercise caution when interpreting data. In this regard, the above reports are important for journalists as they spell out some of the variables and challenges affecting this type of data collection. Regional averages, in particular, can obfuscate significant differences among countries and encourage assumptions.

The World’s Women 2020 report acknowledges, for instance, that “some issues with comparability persist owing to the absence of agreed international definitions in historical data, as well as inconsistent age ranges used in different surveys.”

Similarly, an article in the Medical Journal of Australia11 stressed that available data can vary significantly based on definitions used and the source of public data, such as police, hospitals, courts, community surveys, and clinical studies, among others.

In addition to seeking reliable sources of data, journalists conducting research may also want to explore some of the underlying causes and other factors that contribute to specific incidents or patterns of domestic violence that they are reporting on. It is especially important that these factors be part of an explanatory process, and not perceived as justifications. The multiple causes and predictors of such violence are also key to addressing measures needed to reduce its prevalence.

DECONSTRUCTING CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

Root causes

- Gender inequality, derived assumptions of relative value and worth, and sexist stereotypes

- Normalization of spousal roles and “rights” that endanger the autonomy and safety of women

- Normalization of domestic violence, especially when specific forms of violence are condoned, such as wife beating and marital rape

- Men’s sense of entitlement to a position of power and coercive control within the family

- Impunity (perpetrators not condemned or punished, perception that women are legitimate targets of violence, and victim-blaming)

- Perception of domestic violence as a “private matter”

- Objectification of women, especially through portrayals of women in entertainment and news media, as well as advertising

Conducive contexts

- Previous/ongoing exposure to violence in the home

- Economic insecurity and deprivation

- Discriminatory access to education, employment, land and property rights

- Inadequate social policies and laws

- Lack of access to DV resources and remedies, including barriers to reporting

- Guardianship laws imposing, for example, travel limitations

- Lockdowns and curfews, such as those resulting from epidemic/pandemic restrictions

- Natural disasters

Contributing factors

- Age

- Substance abuse

- Homelessness

- Poor health, including mental health issues

- Child abuse

- Threats of separation or divorce

- Disabilities

- Unemployment of men that results in their inability to provide for the family

It is further worth noting that many country-level statistics do not reflect the increased vulnerability of marginalized communities, and therefore can hide the roots, interaction and impact of multiple risk factors. This was especially well demonstrated in a 2020 report on Native Hawaiians at risk of IPV during COVID-19.12 It states:

“It is inappropriate to infer that the higher incidence of intimate partner violence experienced by Native Hawaiians is attributable to intrinsic characteristics and/or cultural values and practices. Similar to other native peoples, the higher rates of violence cannot be divorced from oppressive external conditions such as colonization, denial of self-determination, racialized system and structures, and economic stress.”

Addressing the prevalence of domestic violence against indigenous women, the World’s Women 2020 report advocated for their inclusion in surveys on violence against women. As an example, it cites a finding from Australia based on 2016 disaggregated data:

“Aboriginal women are 34 times more likely to be hospitalized from family violence and almost 11 times more likely to be killed as a result of violent assault,” the report said.13

7.7.2.3.Improving domestic violence coverage: Three media professionals’ perspectives

A. “Why journalists need to do better in reporting on domestic violence”14

Hannah Storm, is the CEO and Director of the London-based Ethical Journalism Network (EJN). The following is excerpted from a commentary she published on the EJN website on June 12, 2020.

“[Journalists] must ensure they do not reinforce damaging stereotypes, nor perpetuate narratives that blame the person who was abused, and they must give context to the situation, and offer those at risk and facing the reality of domestic violence, the resources they need to be able to access help and support safely. “And yet, we so often see headlines that shift the blame of abuse away from the perpetrator. We see labels and language used to describe the act which deflects from the fact it is a form of abuse and a crime. How often do we see news media using terms such as ‘thwarted husband,’ ‘cheating wife,’ ‘crime of passion,’ or euphemistic references to sex that imply consent rather than rape or sexual assault? How often do we see references to what the woman was wearing, or if she had been drinking, or something else that implies she was somehow to blame for what happened to her? The answer is far too often. Journalists need to recognize that they have a responsibility in their reporting of domestic violence.

“… Many women live in shame, fear, and silence for a long time. As journalists, it is not up to us to question why a survivor might have taken so long to break her silence. It is up to us to see this as a valid response to violent abuse. By extension, journalists must understand the need to minimize harm for survivors and for others who have found themselves impacted by the legacy of domestic abuse.

“Ethical journalism needs to be rooted in accountability, humanity, and accuracy. We have a responsibility to be accountable to our audiences and to ourselves, and where others within our industry fall foul of these principles we need to call them out … The media has a responsibility to recognize the impact its reporting has. The media has a responsibility to be better at covering issues that continually undermine women, that reinforce misogyny, that give rise to gendered violence.”

B.“How do we improve our reporting?”

Handbook contributor Margaret Simons is an Australian independent journalist and writer.

BY MARGARET SIMONS, MARCH 2020

On the morning of 19 February 2020, Hannah Clarke, 31, and her three children were on their way to school when the children’s father leapt into the passenger seat of their car, doused them all with kerosene and set them alight, before taking his own life. The children died on the spot. Clarke died in hospital.

It was an awful example of the most common kind of gender-based violence in Australia – intimate partner violence, or what some call domestic violence. And while the media reports were full of grief and outrage, some well-worn tropes were trotted out.

Had the perpetrator been “pushed too far,” some media reports asked. Or, at the other extreme, the murderer was described as a “senseless monster.”

“We blame the monster, rather than the man … and the society that allowed these murders to unfold” gender violence researcher Annie Blatchford said. “All at the expense of the broader and blatantly obvious problem of domestic violence which sees on average, one Australian woman murdered every week.”15

Australian journalism on intimate partner violence, like much across the Western world, has persistent faults. First, there isn’t enough reporting. Homicides make the headlines but most of the violence, including coercive control and psychological abuse, is still regarded as a private matter, taking place out of sight of both law enforcement and media.

When particularly violent cases draw a lot of media attention, there is victim blaming, sensationalizing and attempts, as with the Clarke case, to rationalize it as the work of “monsters.”

How do we improve the reporting?

I have led a research project aimed at answering that question. We studied media reports, and interviewed editors, producers and reporters at outlets where the reporting had improved.

It won’t come as a surprise to working journalists that we found sources are the biggest single influence on reporting.

First, there is the police force – always an important source. It was when police in the state of Victoria began collecting statistics in a new way, separating out the recording of domestic violence cases, that the extent of the problem became visible to local reporters and editors.

Another, less traditional but increasingly important source was social media. When an outlet reported on intimate partner violence, it got a big response from readers and viewers, many offering stories from personal experience. Newsrooms took social media response as a sign that their audiences were ready to hear more – and that this was an issue of direct relevance to them.

Finally, there was the role of individual newsroom leaders and journalists. In all the cases we studied where reporting had improved, there were one or two newsroom leaders – editors, producers and senior reporters – who had driven and led that change.

Sometimes they had personal experience of the problem. More often, they were confronted by a particularly awful incident, and made the key shift from seeing this not as exceptional and unusual, but as a high-water mark of a pervasive social problem.

To sum up, we found the main drivers of improved reporting on intimate violence were:

- Availablity and attitude of sources

- Influence of social media responses to media outputs, and how this was understood within newsrooms

- Influence of individual journalists and newsroom managers

- Individual incidents of family violence, and how these came to be perceived within newsrooms as evidence of a widespread social problem.

We found that guidelines or “how to” sheets aimed at journalists had limited effectiveness unless they were part of a broader effort, including training.

On the other hand, we had success with using social media to foster a peer-to-peer conversation among journalists on the challenges of intimate partner violence reporting. Better reporting resulted, using a wider variety of sources.

Meanwhile, our research helped spur efforts by the Australian federal advocacy body Our Watch16 to fund media training for victims and survivors of domestic violence, so they can be supported in becoming a new kind of “expert” source.

It would be wrong to suggest that the problem is fixed. As the reporting of the Clarke case shows, the nature of intimate partner violence is still widely misunderstood and misrepresented by the Australian media.

On the other hand, there was also a great deal of responsible and socially aware reporting of this awful case – reporting I don’t think would have occurred just a few years before.

It is too soon to say with confidence that media practice is improving – but at least we have some insights on how to get there.

C. “Giving a voice to survivors”

Handbook contributor Eunice Kilonzo is an award-winning journalist and content generation manager who formerly worked for the Daily Nation (Kenya).

BY EUNICE KILONZO, JUNE 2020

Reporting on gender-based violence is not the easiest. It is tough. It is disheartening. Listening to the survivors — male or female — is a stark reminder of how closely and commonly such violence exists behind closed doors.

One such case was that of Jackline Mwende, whose hands were chopped off by her husband because of a childless marriage. I learned about her story, by chance, one Sunday afternoon in 2016 while on an otherwise uneventful shift. My colleague had just visited her in a hospital and posted a brief and some of her photos on a work WhatsApp group. It was barely 150 words, but I remember reading it repeatedly. I was shocked. The attack not only left her without hands, but her swollen face had stitches crisscrossing her hairline, eyes, and neck. Later, we discovered that she had lost some teeth and hearing in one ear as a result of the attack.

Her story was more than a brief, I thought. She was alive. Could we hear her story, from her own voice? With the guidance of our colleague, I set out — alongside a driver and the then-photo editor — on the over 100 kms (60 miles) journey to meet Mwende. We tracked her down at her father’s compound, about an hour and a half from Nairobi.

Of all my stories, this was the hardest interview to do. How do I ask questions with tact -- in a way that doesn’t reactivate her pain and grief, and cause additional trauma? No one trains you about how to do this kind of reporting. You learn on the job – a tough and dicey place to be.

We got the story; I filed it and went back home.

I woke up the next morning to calls and texts from my peers, asking for Mwende’s contact information. I got emails from organizations, government officials, philanthropists all asking how they could help. The article was picked up by other media houses, political leaders were talking about it; it was a hot topic of national discussion. I was glad that we were having the discussion, not just of the violence but other underlying issues, such as infertility, human rights and the role of our legal system. Gradually, it brought to the fore the different gender perspectives and understanding of GBV in Kenya. Some readers and callers sympathized with Mwende, but were quick to ask: “But what exactly did she do to her husband?” There were deeply-rooted beliefs of male supremacy (and the inverse, powerlessness of women) held by both genders in varying degrees.

The seesaw nature of opinions, not just in the country but among my colleagues in the newsroom, showcases how tough and misunderstood GBV was. Some pushed to tell the story while failing to call it gender-based violence, while others, like myself, opted for a semblance of a survivor-centered approach, where Mwende was at the center of the reporting process.

It was a tough balance, especially in the follow-up articles on Mwende. They included how she got support to go to South Korea to get prosthetics, a new house and seed funding to start a business. I always asked myself, how is this in her best interest while doing no harm, nor exposing her to stigma?

That story paved the way for me to truly understand my role as a journalist: the duty to inform; respect for privacy and confidentiality; ensuring that the reporting is sensitive as it is factually right; thoroughly informing the source of the consequences of appearing in the media; being objective in the reporting and, therefore, not judging, discriminating, and apportioning blame on the survivor.

I am also sensitive to the dilemmas of writing some of these important stories: How soon is too soon to interview a survivor? How do I keep my biases in check? How about my language, diction, and am I using the correct terminology? But more importantly, how do I write in a way that does not shift the focus away from the survivor?

The link to Eunice Kilonzo's story in the Nation (2016) is: https://nation.africa/kenya/news/bat- tered-woman-says-why-she-remained- in-abusive-marriage-1223988

7.7.2.4.COVID-19 pandemic and the surge in domestic violence cases

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, on March 8, 2020, BBC World Service was one of the first major media organizations to sound the alarm about the impact of COVID-19 on the lives of women.17 Increasing instances of domestic violence were identified as one of the five main areas of concern. The others included: school closures, risks faced by frontline care workers and migrant domestic helpers, and longer-term economic impact.

Reports of domestic violence initially surfaced on Chinese social media.

“The coronavirus pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges, as victims were stranded inside their homes with no help from the outside world available,” the SupChina news platform reported. “Meanwhile, for survivors seeking protective orders from courts, counseling and legal services have been largely inaccessible.”18

The Guardian’s early global coverage of the impact of pandemic restrictions is a good example of the importance of the role of journalists in alerting their audience to the scope and severity of the domestic violence crisis:

“Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence” – March 28, 2020

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence

“Calamitous: Domestic violence set to soar by 20% during global lockdown” – April 28, 2020

Contemporaneous coverage by the New York Times highlighted the need to report on the worsening forms of domestic violence, which led to an increased use of the term “intimate terrorism,” referring to the trauma of coercive and controlling aggression:

“A new COVID-19 crisis: Domestic abuse rises worldwide” – April 6, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html

Media outlets also played an important role in highlighting trends in global responses (including relief measures) to what some started naming as the “other” pandemic: gender-based violence. Al Jazeera, on April 25, 2020, published an especially insightful piece by Bonita Meyersfeld, editor of the South African Journal on Human Rights. She wrote:

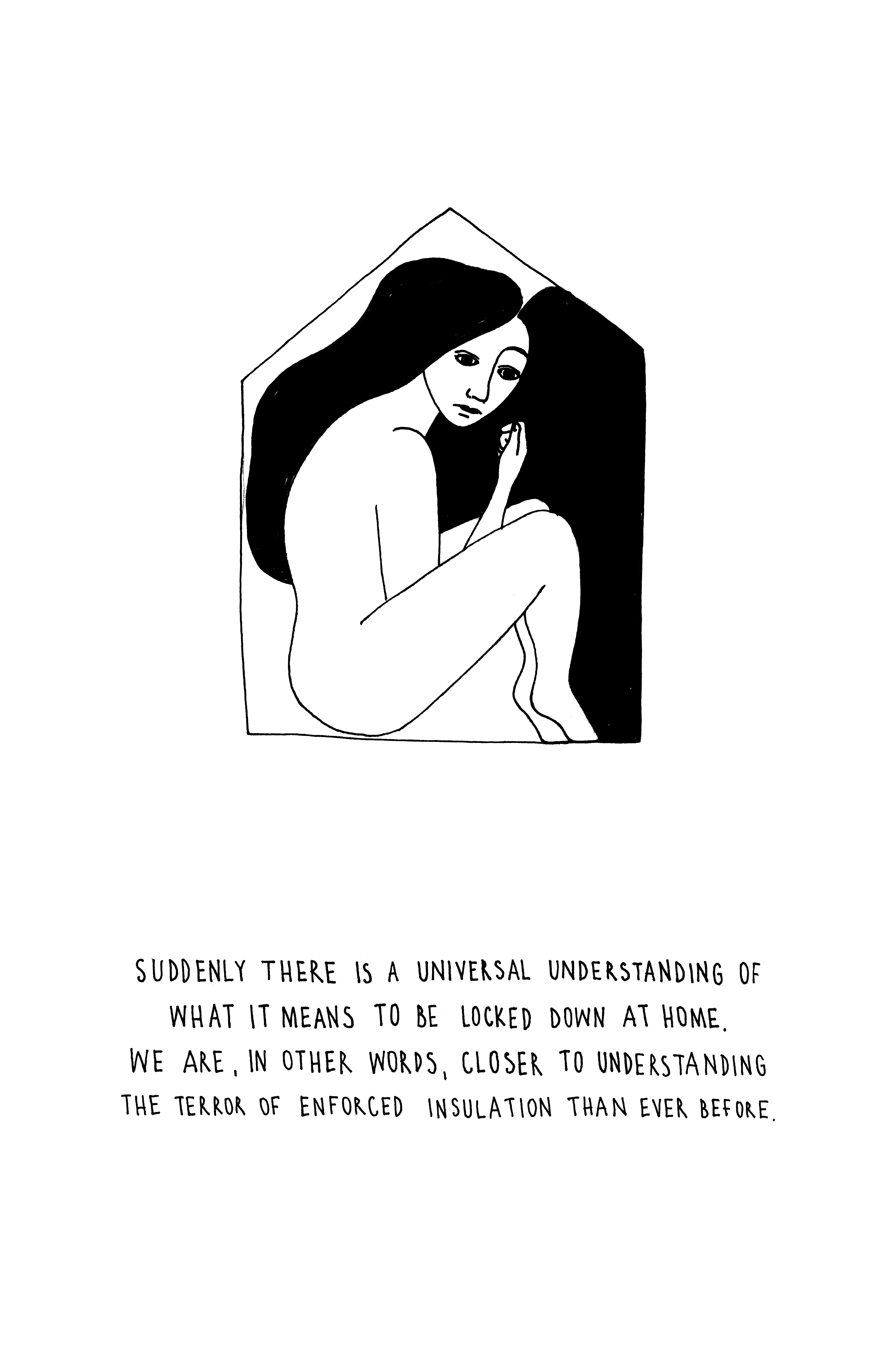

“Before the global lockdown, most governments did little to combat gender-based violence. … The global lockdown has seen a type of intervention in domestic violence cases that is most unusual. For the first time, a handful of states are creating, funding and implementing some very clever steps to help women locked in abusive homes. … The conflation of physical violence, mental manipulation and threats of harm, form a barrier to liberation that can be as restrictive as prison walls. … One must ask why it took a pandemic to focus leaders’ minds on another pandemic (gender-based violence) and the gritty details of interventions that will actually work for victims. I speculate that one of the reasons is that suddenly there is a universal understanding of what it means to be locked down at home. We are, in other words, closer to understanding the terror of enforced insulation than ever before.”19

Suddenly there is a universal understanding of what it means to be locked down at home. We are, in other words, closer to understanding the terror of enforced insulation than ever before.

Two days later, by contrast, The Diplomat, an international current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific region, focused on the gaps in India’s efforts to mitigate the impact of the pandemic:

“Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s eager and abrupt lockdown policy came down with many gender blind spots – putting the country’s most vulnerable at a disproportionately greater risk than others. Women remained largely absent from the government’s COVID-19 policy in spite of the uptick in intimate partner violence and the knowledge that in India, a woman is subjected to an act of domestic violence every 4.4 minutes.”20

Journalists referring to the surge in domestic violence during the pandemic may want to pay particular attention to some of its underreported aspects:

- Increase in domestic burdens and responsibilities, such as care giving and home schooling, which reinforce inequitable divisions of labor

- Exacerbation of pre-existing challenges, such as access to food and water, and to domestic violenc services

- Lack of female participation in decision-making related to the management of the crisis

- Impact of prolonged periods of isolation and abuse on women’s mental health

- Disappearance of informal sector jobs affecting the survival of a majority of women workers such as street/market vendors and domestic workers

- Intensification of the violence and severity of its associated risks, as described, among other media, in a study from Zimbabwe covered by Radio France International21

- Connections with previous crises, such as natural disasters, that illustrate ongoing patterns and inadequacies, especially in terms of governments’ responses and reporting standards

7.7.2.5.Reporting on domestic violence laws and policies

References to relevant domestic laws and policies can greatly enhance the quality and impact of media reporting on domestic violence. The following examples from Cyprus, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, Indonesia, and the United States feature best practices that contextualize media coverage of domestic violence and bring up a wide range of key issues, from contributing factors to remedies, and from prevention to prosecution.

A. “Real progress in North over domestic violence”

Cyprus Mail, Jan. 20, 2020

https://cyprus-mail.com/2020/01/20/real-progress-in-north-over-domestic-violence/

The article discusses a significant rise in victims’ reports of domestic violence since 2018, which “signals an important boost in confidence that justice will be served,” not an increase in violence. This trend was attributed to 2014 amendments to the legal code that criminalized gender-based violence and resulted in the police adding a specialized gender equality unit and a violence intervention unit.

That Mail article by Lizzy Ioannidou reflects many of the best practices to enhance domestic violence coverage by including multiple perspectives:

- Impact of government actions or inactions

- Analysis of statistics and trends

- Implementation of new laws and policies, including both positive results and remaining obstacles. (In this case, high rents and low wages were preventing women from fleeing their abusers.)

- The cycle of violence

- Obstacles to filing complaints

- Availability of services, such as shelters

- Human rights perspective, such as referring to a recent UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women Committee report

- Perspectives of local experts, such as advocates and service providers

B. “Decriminalisation of domestic violence in Russia leads to fall in reported cases”

The Guardian, Aug. 16, 2018

This follow-up article on a reverse trend examined the impact of the law amended 16 months prior that decriminalized certain forms of domestic violence. (Russian law does not treat domestic violence as a stand-alone criminal offense.)22

C. “French women demand action amid high domestic violence rate”

Associated Press, Nov. 22, 2019

https://apnews.com/3556845f3ab74186a26ec6d10739f9ca

The article reports on the French government’s announcement of “measures that are expected to include seizing firearms from people suspected of domestic violence, prioritizing police training, and formally recognizing psychological violence as a form of domestic violence.” Reporter Claire Parker also wrote that “European Union studies show France has a higher rate of domestic violence than most of its European peers.”

D. “Domestic abuse bill condemned for ignoring ‘gendered nature’ of violence amid austerity cuts”

The Independent, July 16, 2019

Maya Oppenheim, Women’s Correspondent of the UK Independent, reports on a domestic abuse bill, which “has been roundly condemned by campaigners for not recognizing the ‘gendered nature’ of domestic violence.”

“Women are more likely to have sustained physical or emotional abuse, or violence which results in serious injury or death,” a Women’s Aid representative told Oppenheim. “Violence against women is rooted in gender inequality. It is essential that this is explicitly recognized in the domestic abuse bill. To solve any complex social problem, we have to start by defining it, and we know that a gender-neutral definition does not work for this highly gendered issue.”

E. “In Bali, a woman’s feet were cut off: #MeToo time for Indonesia?”

South China Morning Post, Nov. 25, 2018

https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/people/article/2174642/bali-womans-feet-were-cut-metoo-time-indonesia

Published on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, this article addresses the issue of “a deep-rooted culture of victim blaming” in Indonesia resulting in the dismissal of domestic violence claims. Significant increases in such violence are also attributed to the fact that “the bill for the elimination of domestic violence has been stuck in Indonesia’s national legislature for 14 years. This bill to promote human rights, achieve gender equality, protect survivors of violence and punish offenders has clearly not been a top priority for the government.”

F. “Public comment ends for proposed changes that eliminate gender-based asylum”

The Fuller Project, July 15, 2020

https://fullerproject.org/story/asylum-regulations-women-girls-domestic-gender-violence/

Investigative journalist Erica Hellerstein reported for the Fuller Project, a global nonprofit newsroom dedicated to reporting on women, that the coronavirus pandemic had diverted Americans’ attention from regulations that would eliminate the possibility of obtaining political asylum on grounds of domestic violence. They seem to specifically target the increasingly high number of women fleeing gender-based persecution from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

G. “In Puerto Rico, an epidemic of domestic violence hides in plain sight”

Gen (Medium publication), June 29, 2020

In this article, journalist Andrea González-Ramírez investigates the response of the Puerto Rican governmental entities following hurricane Maria (September 2017) and subsequent disasters, including the COVID-19 pandemic:

“The cascading crises have given new urgency to the longstanding problems in how the police and courts respond to domestic violence, along with the underfunding of victim services. And they have highlighted how the government’s misguided response continues to leave the island’s women vulnerable.”

7.7.2.6.Selected guidelines to report on domestic violence

United Kingdom

Media Guidelines on Violence Against Women

Published by the Scottish charity Zero Tolerance (2019 edition)

https://www.zerotolerance.org.uk/work-journalists/

Media guidelines for reporting domestic violence deaths

Online publication of the feminist organization Level Up (2018)

https://www.welevelup.org/media-guidelines

Kosovo

Reporting on Domestic Violence: Guidelines for Journalists

Published by the OSCE Mission in Kosovo (2018)

https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/9/2/404348.pdf

Australia

How to report on violence against women and their children

Published in 2019 by Our Watch, an independent NGO established by the Victorian and Commonwealth Governments

Domestic and Family Violence: A Media Guide

Published by the Queensland Government (reform program to end domestic and family violence)

“Survivors of violence: The dos and don’ts of reporting their stories”

by Loni Cooper (2016).

Available through the “Uncovered” website, a project of the Centre for Advanced Journalism at the University of Melbourne.

https://uncovered.org.au/survivors-violence-dos-and-donts-reporting-their-stories

Advisory Guideline on Family and Domestic Violence Reporting

Australian Press Council (2016)

New Zealand

Reporting Domestic/Family Violence: Guidelines for Journalists

Developed by Stephanie Edmond and Sheryl Hann for New Zealand “It’s Not OK” campaign.

http://www.areyouok.org.nz/assets/AreyouOK/Media/Guidelines-for-Reporters.pdf

United States

Online guide for journalists covering domestic violence

Rhode Island Coalition Against Domestic Violence (2015)

7.7.2.8.Endnotes