Abigail Echo-Hawk

8.Training, Ethics, and Glossary Resources

Changing minds and shifting narratives is never easy; it takes time and resolve. Following CWGL’s regional consultations, a number of women journalists from around the world became media trainers, working to lead change and promote good reporting in their own countries and regions.

Teaching best practices on gender-based violence reporting requires creative diligence and ingenuity. The stories below from women journalists turned media trainers in Syria, Yemen and India, show how the lessons gathered together in this guidebook are already being disseminated across the world.

8.8.1.Training media to report on Gender-Based Violence in conflict areas

Handbook Contributor Fahmia Al-Fotih was UNFPA Yemen Communication Analyst when she trained journalists in that country. She now works at UNFPA Liaison Office in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as a Communication and Knowledge Management Specialist.

BY FAHINA AL-FOTIH, JULY 2020

Brutal and prolonged conflicts, such as the one in Yemen, negatively impact media reporting. Due to the nature of the conflict, local media have become more politicized and humanitarian issues have been minimized. A Yemeni study published by the Studies & Economic Media Center found that humanitarian stories, including gender-based violence issues, accounted for only 7.5% of the coverage sample. That category of news has been marginalized and ignored by media since the Yemeni Crisis erupted a decade ago. There is no consideration or attention given to the poor and needy, particularly women and girls, who have most suffered from the conflict.

Journalism constitutes one of the few available avenues through which gender-based violence survivors can share their stories and voice their agony. Unfortunately, journalists can inadvertently become part of the problem when they fail to adhere to basic principles of ethical reporting, particularly when the pursuit of politicized and sensational stories is often prioritized.

To counter such coverage, the UNFPA Yemen country office has organized journalist trainings since 2017 to discuss ethically and sensitively covering gender-based violence in humanitarian crisis settings. The reporters have been able to share ideas, ask questions, and gain insights that could lead to more professional GBV coverage. The trainings are meant to equip journalists to thoughtfully handle these issues, and to protect the safety and lives of survivors who wish to speak out.

Television shows, print articles and more than 10 radio programs dealing with gender-based violence were produced or published after the first training. The “Voices of Women” radio program featured survivors of gender-based violence, as well as lawyers, psychologists and other experts.

One of the survivors said in a radio program that she had been subjected to sexual violence by her husband – and she blatantly called it rape. That was strikingly bold. We never imagined in such a conservative society as Yemen – where gender-based violence terminology is not yet accepted – that a woman could come forward and speak about marital rape.

That inspired us to continue and train more media. The trainees are usually from all forms of media and represent both regional and international media houses. During the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence in 2020, we targeted new journalists, who were about to graduate from university.

It is always helpful to provide informative and durable tools to which journalists can refer during the reporting process. So, we produced a small brochure and short video clip in both Arabic and English. The journalists were able to save it in their own mobiles and keep sharing it via WhatsApp, while some trainers have used it in their media training. We also screened this clip for a meeting of the subcluster of NGOs and UN agencies coordinating gender-based violence humanitarian action, and many of those participants requested that we share it with them. They said the Nine Ethical Principles published in 2015 by UNFPA for reporting on gender-based violence are not only useful for media personnel but also for humanitarian organizations. In addition, some UNFPA offices in the region asked that we also allow them to use the short clip in their training programs.

After the 2019 International Conference on Population and Development, which was convened by UNFPA, graduates from our previous journalist trainings formed a network to contribute to fulfilling the outcomes and commitments of the conference.

The network has created an annual competition, International Conference on Population and Development Best Story, with entries that adhere to the Nine Ethical Principles. In 2020, we received hundreds of submissions. They were all so good that it was hard to select winners. What makes me proudest is that the members of the network are really committed, and they keep producing more stories. They have embraced gender-based violence issues to their hearts and understand the imperative to protect the safety and lives of gender-based violence survivors.

We were unable to conduct face-to-face trainings in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The UNFPA instead conducted four virtual trainings for journalists on ethical reporting and how COVID-19 has deepened the vulnerabilities of gender-based violence survivors. Despite connectivity challenges, the virtual trainings have brought together journalists from different governorates across the country, which would have been logistically difficult if the training had been done in-person, given the nature of the conflict in Yemen. The virtual trainings provided ample room for the exchange of ideas, experiences and stories.

More than 50 powerful stories have been produced showcasing the impact of COVID-19 on gender-based violence and reproductive health services. The story angles have highlighted inequalities and specifically the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on women and girls. For example, a story shed light on how funerals took place for the men who died of COVID-19, but not for the women. Other stories showed how lockdowns were unfairly imposed only on women-owned businesses, and how family elders, who feared contracting COVID-19, started writing wills that purposely disinherited female heirs. Pandemic-related increases in domestic violence, divorce rates and the impact on mental health of gender-based violence survivors were all reported in the stories.

All these trainings that UNFPA has done over the years have helped build a solid foundation for specialized journalism in Yemen and created a network of journalists who are experts on reporting on gender-based violence. Ultimately, the 300 journalists who have been trained since 2017 are equipped to explore underreported stories, while better understanding the impact of coverage on survivors and communities, as well as how to use best practices when it comes to the actual reporting.

In addition, these trainings have influenced the media to more ethically report on humanitarian issues in Yemen. We are honored to see that other UN agencies have started replicating this model of media engagement.

These trainings have influenced the media to more ethically report on humanitarian issues in Yemen

Gender-based violence training for journalists (September 2019), Hadhramaut Governate of Yemen.

© UNFPA Yemen/SEMC

8.8.1.1.Guiding principles for reporting and training on gender-based violence

Handbook Contributor Milia Eidmouni is the co-founder and former Regional Director of the Syrian Female Journalists Network. She is a Media and Gender Trainer.

BY MILIA EIDMOUNI, JUNE 2020

Reporting on gender-based violence plays a vital role in challenging the patriarchal society, advocating, and lobbying for passage and implementation of effective laws and policies. When I decided to study journalism, my parents didn't accept my choice easily and tried to convince me to go for a "typical career." I was 17 years old and received my parents' concern as part of their "over-protecting attitude." It didn’t occur to me to think: I'm experiencing one type of gender inequality, and how the patriarchal system and culture control women's lives and freedom of choice.

After graduating from journalism school, I followed my passion for covering women's issues. I worked for more than 10 years between reporting, drafting gender policies, and training other women and men journalists on gender-sensitive reporting, believing in the collective work and long- term process, to foster a social change around gender-based violence.

Deep understanding of the root causes of the issue as it connects directly to the political, economic, and social situation in the country will help media workers shift the narrative, challenge the stereotypical image of women in media, and tackle society’s taboos.

Changing the narrative about women and girls came with resistance at first. But it has proven effective to insist that women and girls' rights are also a priority and that providing guidance to media workers to create positive and gender-balanced content can be the first tangible change.

As co-founder of the Syrian Female Journalists Network, I have worked with the emerging Syrian media and journalists from different countries in the region. I have found that the following tips are important for journalists when covering gender-based violence stories:

- Avoid generalization and judgmental language. Language and correct terminology are important pillars in your story, countering stereotypical phrases about violence against women and LGBTQ people that still dominate media coverage. Ensure you are giving minorities and women an active role in your stories, instead of victimizing them, or talking on their behalf. Creating a list of wrong and right terms and phrases will help you to write an ethical report that reflects a human rights perspective.

- Understand the root causes of the issue and question with a critical eye when seeking information from an official organization, nongovernmental organizations and gender specialists. Ask for facts and sources of support and services available for survivors and victims of gender-based violence.

- Keep learning and building your gender-sensitive writing skills. Many media and women's rights organizations provide journalists with training opportunities and guidebooks on how to cover gender-based violence from a human rights perspective. You can enroll in this training and get to share your experience and gain insights from other colleagues and experts.

- Be aware that gender issues are not only women's stories. Using a gender lens, search for the invisible stories of struggle that minorities face too, such as: gender-based violence committed against the LGBTQ+ community, refugees, girls and men. Each voice matters, and your report might challenge the social norms and press for changes in discriminatory laws.

- Do No Harm. When interviewing survivors of gender-based violence give them the time to decide whether they want to do the interview or not, and explain when and how you will use the story. Respect their privacy, record their voices and take pictures, if needed, after they consent to those activities. It is good to have a psychosocial support expert present during the interview to provide help in case the questions cause re-traumatization.

- Seek legal expert advice for your story, to ensure you are referring to the right laws in your country, and that you will not unwittingly put your interviewee at any kind of risk.

- Make a database of local experts and organizations that provide direct support for gender-based violence survivors. This database will help you build a strong and in-depth report, and help you avoid contacting the same expert for all your articles. Make sure you have different voices and genders, based on the angle of your story and the type of information that each source provides.

The media coverage on gender-based violence is increasing in the Middle East and North Africa region, thanks to the women and feminist movements, and women-led media initiatives. They are taking an important role in tackling the untold stories and amplifying women’s voices from different backgrounds. Media organizations should adopt and create gender quality assurance measures and develop internal policies/ethical guides that promote gender equality and gender justice. What is more, they should do this within their workplace to ensure the media reports are meeting the standards of best practices to cover gender-based violence stories.

8.8.1.2.Training rural women to use digital story-telling against gender-based violence

Handbook Contributor Stella Paul is an award-winning journalist from India. She works as an Inter Press Service reporter and as World Pulse Global Lead Trainer.

BY STELLA PAUL, JUNE 2020

“I don’t know why a man thinks he has the right to hurt a woman,” says Madhuri Deshkar – a sarpanch (head of a village council) turned women’s rights activist in Bhandara district of India’s Maharashtra state. As a grassroot leader, Deshkar has never shied away from calling out those perpetrators of gender-based violence, but she usually spoke at meetings and social events within her community. Lately, however, she has taken a new route to express her thoughts and opinions: digital storytelling.

Pratibha Ukey is also an activist based in the Nagpur district of Maharashtra. Single women like her in Nagpur are often deprived of property rights by relatives, forcing them to struggle for survival. Ukey has also begun to write against this discrimination using digital tools.

Minakshi Birajdar is from the Aurangabad district of Maharastra. As a young widow, she was ridiculed and humiliated for being a social activist which caused her mental stress and pain. Today, besides economically empowering women of her community, she is using digital storytelling to raise awareness against GBV.

Deshkar, Ukey and Birajdar have one thing in common: they are Fellows of the Collective Impact Partnership (https://riseuptogether.org/collective-impact-partnership/) – a project focused on providing support to grassroot women leaders in Maharashtra working on economic empowerment. Twenty-two women were chosen for this project. Each one received a financial grant and was trained in leadership skills and digital storytelling.

As the global lead trainer of World Pulse (www.worldpulse.com) – one of five project partners, I had the joy of training these 22 women leaders. During my training, they learnt digital storytelling, digital safety and digital networking, before being connected with a safe web platform designed especially for them by World Pulse.

It was a challenge from the very beginning: Despite their vast experience as grassroot leaders, the trainees knew nothing about storytelling. Each of them had a smartphone, but knew nothing beyond phone calls, taking photos and sharing over WhatsApp. And perhaps the biggest of the hurdles was that, although each one of them had a hundred stories to tell, nobody knew how to articulate them. Last but not least, the technical issues about writing on a digital platform seemed too overwhelming a task as they barely understood English.

However, their enthusiasm and passion for being heard by a greater community made up for their lack of digital skills and - after the very first of our training sessions during which I focused on “Nobody speaks for me, I speak for myself” - they began to write their stories.

Nobody speaks for me, I speak for myself

Each one of them had powerful narratives. To begin with, they chose one subject that was truly close to their hearts: gender-based violence.

Madhuri Deshkar wrote about a woman being beaten by a man in broad daylight. When she confronted him, he replied ‘I am her husband,’ implying that he had the authority to treat his wife however he wanted. She then wrote how she got him punished for the crime. It was a courageous act for a woman in a rural society, where women are not expected to challenge a man. The story received great feedback and was commented upon by fellow members who also survived gender-based violence and were now fighting against it. Read the story here (https://www.worldpulse.com/community/users/madhuricip/posts/88483)

In her stories, Pratibha Ukey has been highlighting the plight of women who are wrongly denied property rights. She calls this denial a clear form of gender-based violence since only women experience it, especially widows. “For me, denying a woman her legitimate right to property is gender-based violence that we all need to stand against,” she says. Here is one of her stories: https://www.worldpulse.com/community/users/pratibha-cip/posts/92519

Ukey has also been actively observing the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign (https://www.worldpulse.com/community/users/pratibha-cip/posts/93033).

Minakshi, who fights for the welfare of women whose husbands have committed suicide due to drought and crop failure, writes award-winning stories about climate change increasing the burden of gender- based violence in her community.

Read her stories here: https://www.worldpulse.com/community/users/minakshib/posts/88776

As a trainer, it is both challenging and spiritually fulfilling to see these powerful yet unheard voices finding their own audience, especially on a platform they once knew little about. To see them forging connections and stirring actions on gender-based violence through their stories also is a big motivation.

8.8.2.Selected resources for media educators and trainers

Several of the listed resources were developed with specific national or regional audiences in mind. They were selected for this chapter, however, because of the broader relevance of their content and tools regarding gender-based violence reporting.

AFRICA

Reporting Gender-Based Violence: A Handbook for Journalists

Inter Press Service (2009)

Editor: Kudzai Makombe

Available in English and French

http://www.ipsnews.net/publications/ips_reporting_gender_based_violence.pdf

Gender-Based Violence Prevention Network 16 Days of Activism Campaign: Media Training Module

Gender-Based Violence Prevention Network (2015)

Sensitization Manual on Media Reporting - Care Balkans (care-balkan.org)

Although developed for advocacy organizations working with the media, this module can also be useful for journalists covering the global campaign on ending gender-based violence. The GBV Prevention Network, based in Kampala, Uganda, is represented in 18 African countries.

EUROPE

Gender Sensitization Manual on Media Reporting on Gender-Based Violence

Care International Balkans (2017)

Gender Sensitization Manual on Media Reporting - Care Balkans (care-balkan.org)

Preparing a Training for Journalists and Students of Journalism

UN Women Bosnia and Herzegovina (2017)

UN woman prirucnik nasilje nad zenama-dodatak EN-WEB.PDF (unwomen.org)

This Training of Trainers publication supplements UN Women’s Media Coverage of Gender-Based Violence Handbook.

MIDDLE EAST

Reporting on Gender-Based Violence in the Syria Crisis: A Training Manual

UNFPA (2016)

Available in English and Arabic

Reporting on Gender-Based Violence in the Syria Crisis: A Training Manual (unfpa.org)

Reporting on Gender-based Violence in Humanitarian Settings: A Journalist’s Handbook

UNFPA (2020)

Available in English and Arabic

Author: UNFPA Arab States Regional Humanitarian Response Hub

https://www.unfpa.org/reporting-gbv-humanitarian-settings

UNFPA produced a companion training video (12 minutes) on the principles and ethics of reporting on gender-based violence.

Reporting Gender-Based Violence: Guidance Material for Journalists

UNFPA Lebanon

This website was developed by Reem Maghribi, and is maintained by Sharq.org, a pan-Arab NGO whose projects focus on media development. Maghribi is a Gender and Communication Consultant and Media Trainer.

Working with Gender-Based Violence Survivors: A Reference Training Manual

UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) (2012)

https://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/working-gender-based-violence-survivors

Although developed for humanitarian frontline workers, this training tool offers useful resources and guidance for journalists working with GBV survivors.

NORTH AMERICA

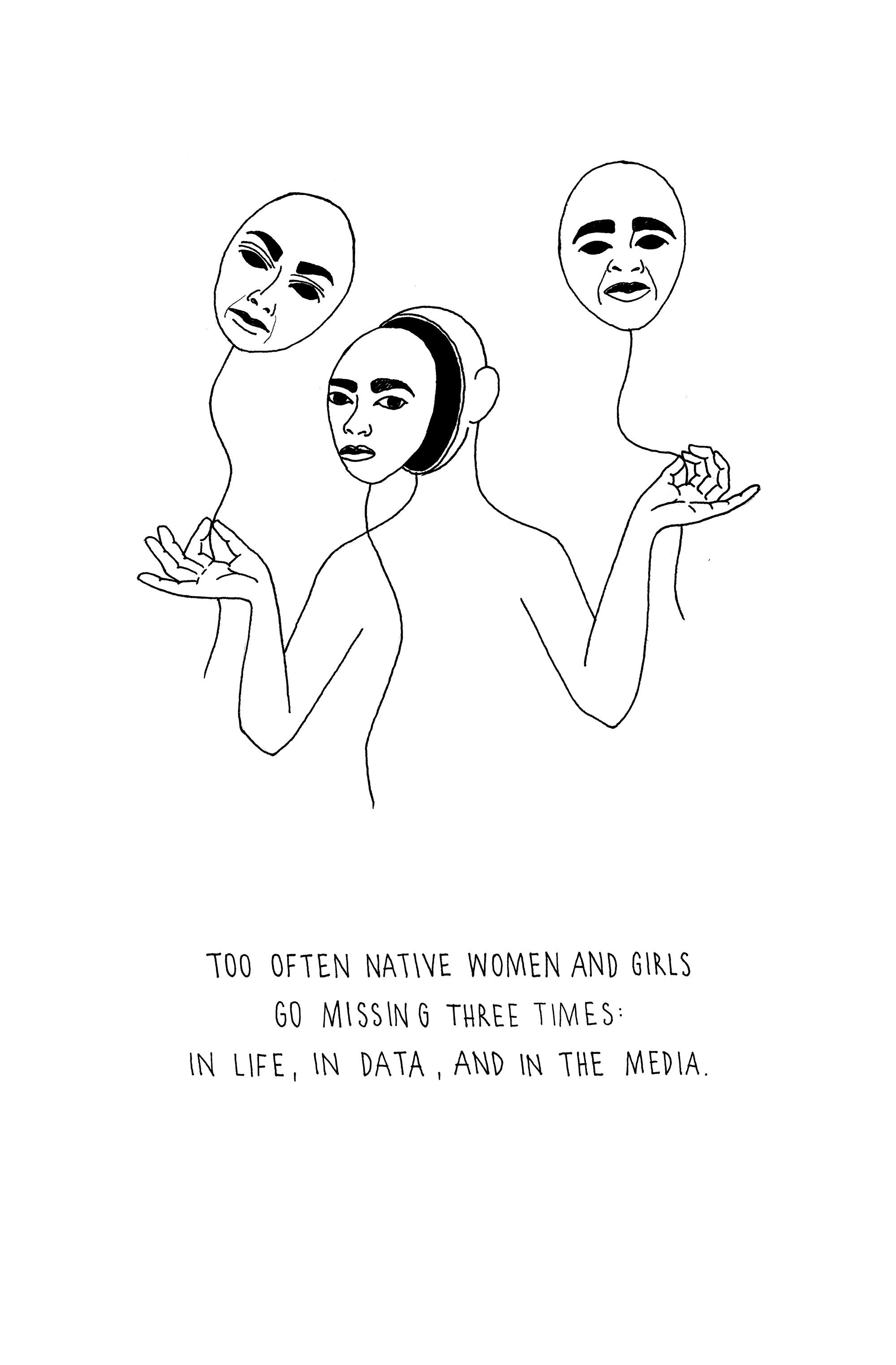

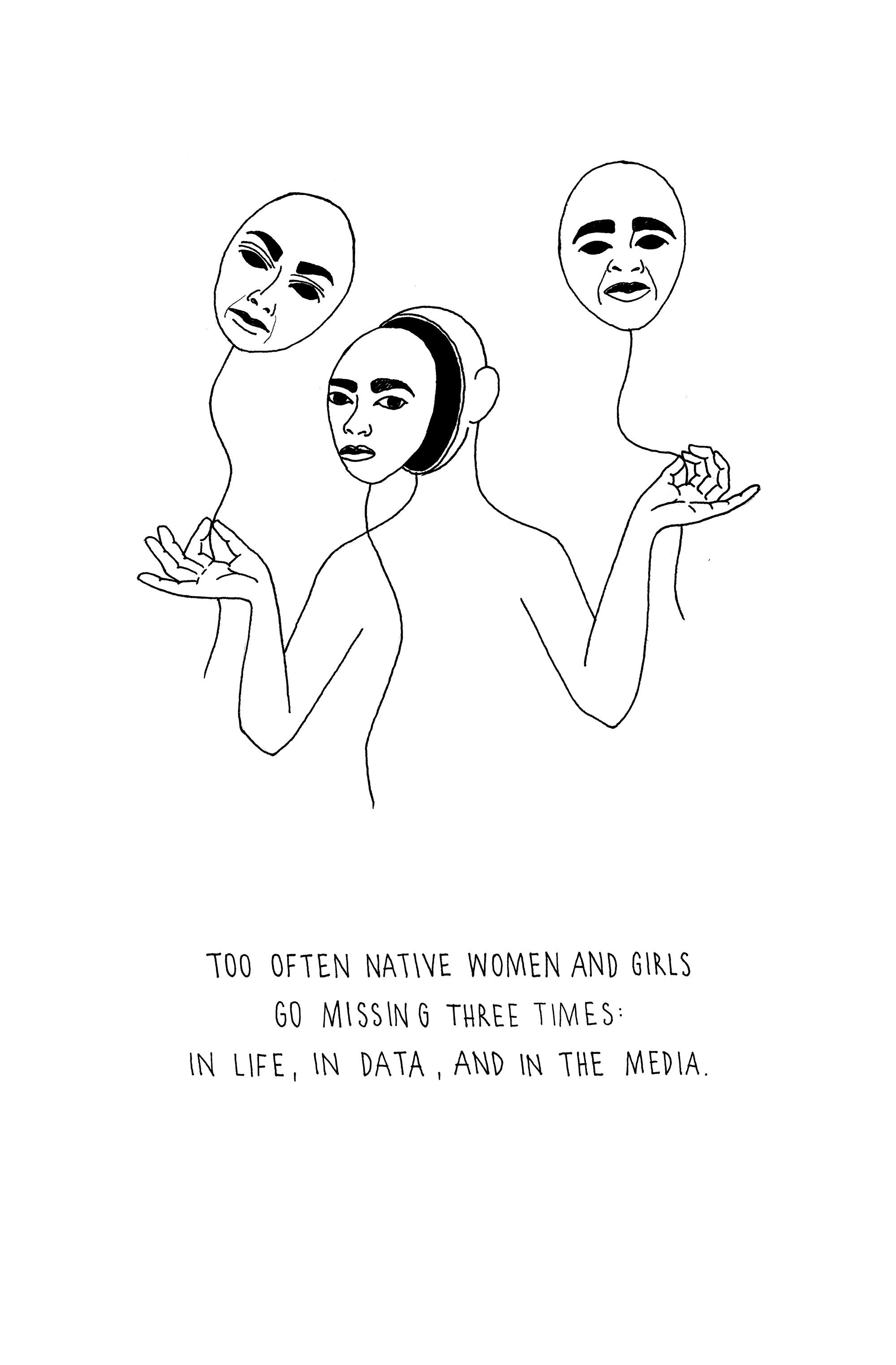

The following resources were selected more specifically for journalists reporting on Indigenous people and communities. This focus stems from the lack of Indigenous voices in the mainstream Canadian and U.S. media, especially around the issue of gender-based violence. As Abigail Echo-Hawk, Chief Research Officer for the Seattle Indian Health Board, said in an interview with the HuffPost “Too often Native women and girls go missing three times – in life, in data and in the media.”

Too often Native women and girls go missing three times – in life, in data and in the media

Indigenous Media Guides

Native American Journalists Association (2021)

https://najanewsroom.com/8724-2/

These brief media guides were developed to help non-Indigenous journalists report on First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in Canada.

NAJA, currently based at the University of Oklahoma in Norman (U.S.), “works across the media industry to ensure accurate and contextual reporting about Native people and communities.”

Reporting and Indigenous Terminology

Native American Journalists Association

Changing the Narrative About Native Americans; A Guide for Allies

First Nations Development Institute (2018)

https://www.firstnations.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/%E2%80%A2MessageGuide-Allies-screen-spreads_1.pdf

The First Nations Development Institute (based in Colorado and New Mexico, U.S.) designed this tool as “a quest to replace false narratives.” Although not developed specifically for the media, it can help journalists dispel myths and misconceptions.

8.8.3.Media Ethics Guidelines

Several of these resources do not specifically cover gender-based reporting. But many of their broader principles are applicable and can be used in gender-based violence media trainings or courses.

Codes of Ethics

Accountable Journalism website (hosted by the Reynolds Journalism Institute of the Missouri School of Journalism in the U.S. and by the Ethical Journalism Network)

Accountable Journalism & Codes of Ethics - Ethical Journalism Network

A unique and comprehensive “compilation of international codes of media ethics from around the world.”

This is a searchable database.

Global Charter of Ethics for Journalists

International Federation of Journalists

https://www.ifj.org/who/rules-and-policy/global-charter-of-ethics-for-journalists.html

IFJ Guidelines for Reporting on Violence Against Women

International Federation of Journalists

Learning Resource Kit for Gender-Ethical Journalism (2012)

International Federation of Journalists and World Association of Christian Communication

Includes a survey of media policies and codes from over 30 countries.

Ethical Journalism Network (EJN)

This UK-based international network offers the following relevant online courses:

-

The Ethical Journalist’s Toolkit

Developed in collaboration with the Thomson Foundation

The Ethical Journalist's Toolkit - 1st version (edcastcloud.com)

-

Photographer’s Ethical Toolkit

Developed in collaboration with the Thomson Foundation and the Photography Ethics Centre.

https://thomsonfoundation.edcastcloud.com/learn/the-photographer-s-ethical-toolkit-self-paced-6636

Ethical Reporting on Domestic Violence (EJN)

Nine Ethical Principles: Reporting Ethically on Gender-Based Violence in the Syria Crisis

UNFPA Regional Syria Response Hub (Amman, Jordan)

8.8.4.Glossaries

The recent publication of comprehensive glossaries dedicated to gender-based violence terminology led CWGL to compile a selection of those currently available in English and online, instead of creating its own.

GENERAL GLOSSARIES

Sexual and Gender-Based Violence: A Glossary from A to Z

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), (2020)

Available in Arabic, English, Farsi, French and Spanish, 110 pages

https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/atoz_en_book_screen.pdf

The glossary includes detailed definitions of 61 essential words. Its audience includes journalists.

“While words can help give survivors of sexual and gender-based violence visibility, truth, and justice, they can also discriminate, re-victimise, and destroy,” Guissou Jahangiri, FIDH Vice-President, wrote.

While words can help give survivors of sexual and gender-based violence visibility, truth, and justice, they can also discriminate, re-victimise, and destroy

Gender-Based Violence Terminology

Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children, Western University, Ontario, Canada.

http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/docs/LearningNetwork-GBV-Glossary.pdf

Two versions are available: the PDF version can be downloaded (96 pages), or the definitions (185 terms) can be accessed by clicking on the appropriate alphabet letter.

Women’s Human Rights

Swiss Government in collaboration with the Swiss Centre of Expertise in Human Rights, the University of Bern, and the Berlin-based IT company Lucid.

This free app provides a comprehensive terminology database, including definitions of keywords related to gender-based violence with links to relevant UN documents.

Violence Against Women Key Terminology

UNFPA Asia and the Pacific (2016), 12 pages

https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/violence-against-women-key-terminology-knowvawdata

ISSUE-SPECIFIC GLOSSARIES

Glossary of definitions of rape, femicide, and intimate partner violence

European Institute for Gender Equality (2017), 48 pages

https://eige.europa.eu/publications/glossary-definitions-rape-femicide-and-intimate-partner-violence

Glossary on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse

United Nations. Prepared for the UN Special Coordinator on improving the UN response to sexual exploitation and abuse (2017), 20 pages

2nd Edition: UN Glossary on SEA [English]

A Database of UN Resolutions and Expert Guidance on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

Developed by the International Planned Parenthood Federation, Western Hemisphere Region, and the Sexual Rights Initiative (2021)

https://www.unadvocacy.org/#/en/

Each keyword (including under GBV) in this searchable database is linked to definitions in relevant UN documents.

Cyber Violence and Hate Speech Online Against Women

European Parliament (2018), 76 pages

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1ccedce6-c5ed-11e8-9424-01aa75ed71a1

This study by Adriana van der Wilk includes a detailed glossary.

Defining ‘Online Abuse’: A Glossary of Terms

PEN America

https://onlineharassmentfieldmanual.pen.org/defining-online-harassment-a-glossary-of-terms/

SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER IDENTITY TERMS

NLGJA Stylebook

National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (U.S.)

https://www.nlgja.org/stylebook/ (15 pages)

Spanish edition: https://www.nlgja.org/stylebook/espanol/ (10 pages)

GLAAD Media Reference Guide

Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (U.S.) (2016) 40 pages

https://www.glaad.org/sites/default/files/GLAAD-Media-Reference-Guide-Tenth-Edition.pdf

Includes an 11-page glossary

A Guide to Gender Identity Terms

National Public Radio (U.S.), 2021

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/02/996319297/gender-identity-pronouns-expression-guide-lgbtq