Cathy Otten

4.Reporting on sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict settings

Media reports often present gender-based violence in conflict as if it exists in a vacuum. However, UN Secretary-General António Guterres’s March 2021 report to the Security Council examined broader patterns and trends of conflict-related sexual violence as a “tactic of war, torture, and terrorism in settings in which overlapping humanitarian and security crises, linked with militarization and the proliferation of arms, continued unabated.”1 The challenge for journalists is to avoid losing sight of the big picture.

4.4.1.The Bigger Picture

“The extreme violence that women suffer during conflict does not arise solely out of the conditions of war; it is directly related to the violence that exists in women’s lives during peacetime,”2 the UN Independent Experts stated in their 2002 assessment on the impact of armed conflict on women.

The International Crisis Group confirmed this assessment when its Director of Research, Isabelle Arradon, warned: “In ways that can be easy to overlook, conflict can exacerbate pre-existing patterns of gender discrimination and inequality, leaving women and girls with few survival options.”3 Those patterns were clearly illustrated in the 2018 report of the UN Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar:

“In examining the situation of sexual and gender-based violence in Myanmar, the Mission also reviewed the situation of gender inequality more broadly. It found a direct nexus between the lack of gender equality more generally within the country and within ethnic communities, and the prevalence of sexual and gender-based violence.”4

A landmark UN Security Council resolution (S/RES/1325, 2000) called on all member states to take special measures in conflict settings to protect women and girls from such violence, especially rape and other forms of sexual abuse. The Security Council framework on conflict-related sexual violence includes nine follow-up resolutions, the most recent of which was adopted in 2019. This latter resolution (S/RES/2467)5 was hailed by the UN for “strengthening prevention through justice and accountability and affirming, for the first time, that a survivor-centered approach must guide every aspect of the response of affected countries and the international community.”6 This included the explicit recognition of the needs and rights of children born of sexual violence. Resolution 2467, however, fell short of expectations in several important ways:

- The threat of a U. S. veto led to the exclusion from its final language of any references to “sexual and reproductive health” (perceived by the Trump administration as condoning abortion), or to the International Criminal Court’s role in prosecuting perpetrators.

- The final resolution did not include the initial recommendation for the establishment of a U. N. monitoring body, which had been reported in the media (notably by Foreign Policy Magazine, PassBlue, and The Guardian).

- As noted by Liz Ford in The Guardian, “progressive text on strengthening laws to protect and support lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people who could be targeted during conflict” was also removed.7

Conflict can exacerbate pre-existing patterns of gender discrimination and inequality.

Those shortcomings underscore the importance of monitoring both governments’ compliance with human rights commitments and the resistance of many to establish or strengthen protection and accountability mechanisms. Survivors of conflict-related sexual violence are especially at risk to be revictimized by impunity, as well as the lack of transparency and political will.

In this respect, it is important for the media to report on the investigations and landmark prosecution cases of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Rome Statute, which established The Hague-based ICC in 1998,8 defined the following crimes under the jurisdiction of the Court:

- Crimes against humanity, including “Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity.” Article 7 (1) (g)

- War crimes, including the above crimes “and any other form of sexual violence also constituting a serious violation of article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions.”9 Article 8 (2) (e) (vi)

The ground-breaking “Policy paper on sexual and genderbased crimes” published in 2014 by the ICC Prosecutor’s Office10 clarified the scope and implications of the Statute. It emphasized that the Office:

- “Recognizes that sexual and gender-based crimes are amongst the gravest under the [Rome] Statute.

- “Will apply a gender analysis to all crimes within its jurisdiction, examining how those crimes are related to inequalities between women and men, and girls and boys, and the power relationships and other dynamics which shape gender roles in a specific context.

- “Will strive to ensure that its activities do not cause further harm to victims and witnesses.

- “Supports a gender-inclusive approach to reparations, taking into account the gender-specific impact on, harm caused to, and suffering of the victims affected by the crimes for which an individual has been convicted.”11

Those issues can also be reflected in contextual and follow-up reporting by journalists covering such crimes. Landmark ICC judgments and developments in current cases provide an important opportunity to report on their potential impact and more broadly on the critical issues of impunity and accountability:

- Dominic Ongwen case (Uganda): A former top commander in the Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group, Ongwen (whose arrest warrant was issued in 2005), was finally convicted on 61 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes and sentenced in May 2021 to 25 years. Charges included rape, sexual slavery, child abduction, forced marriage, and forced pregnancy. The Guardian highlighted the case as “one of the most momentous in the ICC’s 18-year history.”12 It was indeed the first time that forced pregnancy was prosecuted before an international court, and forced marriage as a crime against humanity at the ICC.

- Bosco Ntaganda case (Democratic Republic of the Congo): The former Congolese rebel leader, indicted in 2006, received a 30-year sentence (the longest handed down by the ICC) after having been found guilty of 18 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including rape and sexual slavery. Ntaganda was the first person to be convicted of sexual crimes by the ICC. The 2019 conviction was upheld by the ICC Appeals judges in March 2021. A previous Appeals Chamber decision (2017) found that it had indeed “jurisdiction over the alleged war crimes of rape and sexual slavery of child soldiers.”13 This decision was hailed as “one of the most important developments in international humanitarian law in the last 120 years where one more impunity gap for sexual and gender-based crimes has been closed.”14

- Al Hassan case (Mali): Al Hassan was the de facto chief of the Islamic Police enforcing Sharia law in Timbuktu, including policies that resulted in the rape and sexual enslavement of women and girls. His trial started in July 2020. According to a June 2021 report by the International Federation for Human Rights and Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice, the achievement in this case is that the charges against him include “the crime against humanity of persecution on gender grounds – an unprecedented charge before the ICC ... . The Office of the Prosecutor alleges that Al Hassan particularly targeted women and girls on the basis of gender, imposing restrictions on them motivated by discriminating opinions regarding gender roles.”15

In contrast with the ICC prosecution of individuals, the International Court of Justice – also based in The Hague – is the principle judicial organ of the UN and a civil court that hears disputes between countries. In 2019, The Gambia filed a case against Myanmar, on the grounds that its military committed atrocities against ethnic Rohingya Muslims, including rape, in violation of the UN Genocide Convention. PassBlue, reporting on this unprecedented prosecution, commented that “the case has the potential to enhance feminist international law, while reinforcing the need to carry out the global women, peace and security agenda.”16

It’s important to note that there are also substantial criticisms of the ICC and international justice framework. Yale Professor Samuel Moyn points out that the ICC was originally promoted by lesser nations, but has since “become a forum for accusing their leaders alone.” Moyn writes that the “rise of international criminal accountability has occurred alongside the eclipse of prior schemes of global justice, which promoted not retributive punishment but social renovation to achieve liberty and equality.” Here, Moyn’s argument allows us to think about a type of social justice reporting that illuminates social ills and pushes for systemic changes that move beyond the focus on retribution and the individual.17

4.4.2.Challenges and setbacks

Political failures and setbacks constitute a huge challenge to the eradication of sexual violence as a tool of war and an inescapable byproduct of armed conflicts, in spite of all the legal protections, government commitments and international mechanisms and regardless of the conflict context.

The complex elements of this challenge – all contributing to the vulnerability and prolonged suffering of survivors – were forcefully summarized by Pramila Patten, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, when she briefed the Security Council in July 2020.18

“Sexual violence is used as a war tactic and a political tool to dehumanize, destabilize and forcibly displace populations across the globe. . . ,” she stated. “Wartime sexual violence as a biological weapon, a psychological weapon, and an expression of male dominance over women sets back the cause of gender equality and the cause of peace. . . . Sexual violence is characterized by staggering rates of impunity and recidivism.”

In addition to the issue of governments’ non-compliance, Patten focused on the diversity of survivors’ experiences which are often dismissed when it comes to policy-making and the provision of funds and services: “When these decisions are not gender-based in their design, they will be gender-biased and exclusionary in their effect.”

When these decisions are not gender-based in their design, they will be gender-biased and exclusionary in their effect

Survivors’ expectations are also too often crushed by delays and setbacks in their quest for justice, as illustrated by the plight of the Yazidi minority in Northern Iraq since 2014. Challenges remain, although the UN Team in charge of investigating the ISIL crimes against Yazidis established in 2021 that those crimes constituted genocide (repeating the legal designation originally made by the UN Commission for the Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic in 2016). Nadia Murad, a Yazidi survivor and co-winner of the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize, concluded in her remarks to the UN Security Council: “Evidence has been found, but we are still searching for the political will to prosecute.”19 The issue highlights ongoing difficulties when it comes to enforcing UN designations, and the frustration felt by many survivors over human rights discourse.

In his March 2021 report on conflict-related sexual violence,20 UN Secretary-General Guterres highlighted some of the most severe challenges: “Over the past decade the level of compliance by parties to conflict remains appallingly low. As noted in the gap assessment included in my previous report [2020], over 70 % of the listed parties are persistent perpetrators, having appeared in my annual reports for five or more years without taking remedial or corrective actions.”

Referring to these annual reports, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, Dubravka Šimonović, noted:

“Of the 19 States monitored by the Secretary-General, only seven states have ratified the [ICC] Rome Statute ... . Of those States that had not, only Myanmar had no statute of limitation for rape in times of peace or conflict. Having a statute of limitation for the prosecution of rape contributes to the widespread impunity for perpetrators.”21

The news site PassBlue, through its independent coverage of the UN, has monitored many such challenges, including those emerging from the annual Security Council debates on sexual violence in conflict. It pointed to the fact that the April 2021 debate, for instance, was to “address victims’ care rather than the responsibility of countries to stop such abuses and prosecute perpetrators.”22

On the occasion of that same debate, the UN LGBTI Core Group (an informal cross-regional group of UN member states) also denounced the lack of compliance and stated that:

“The Core Group underscores the need to ensure that survivors’ rights are respected, and that all victims of sexual violence have access to justice, assistance, reparations and judicial redress ... . Members [states] should recognize that all survivors, including those who are targeted on the basis of their actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity, are unique individuals with different experiences and needs, and that any support to assist and empower survivors must be contextualized, paying particular attention to multiple and intersecting vulnerabilities.”23

In many parts of the world, the impact of the COVID19 pandemic has compounded those challenges and setbacks. In his March 2021 report, Guterres noted:

“The socioeconomic fallout of the pandemic led to the use of harmful coping mechanisms, such as child marriage, as desperate parents living in internal displacement settings in Iraq, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen arranged marriages for girls as young as 10 years old.”

The work of humanitarian service providers, he added, was “impeded by insecurity, access constraints and chronic underfunding, as already scarce resources were redirected towards the COVID-19 response.” This statement echoed the warning previously issued by May Maloney, the Sexual Violence Adviser of the International Committee of the Red Cross, on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women (Nov. 25, 2020):

“When we layer crisis atop crisis – such as an armed conflict with a public health emergency in the context of a global climate emergency – the risks of sexual and gender-based violence spiral, while the available support shrinks and becomes siloed or fragmented.”24

When we layer crisis atop crisis – such as an armed conflict with a public health emergency in the context of a global climate emergency – the risks of sexual and gender-based violence spiral

4.4.3.Peeling back the layers for audiences

Unidimensional reporting falls short of educating the audience about conflict-related sexual violence. No matter how compelling individual stories of suffering are, they provide greater understanding when framed to shed light on root causes, and impacts of abuse and impunity patterns.

The notion that conflicts exacerbate pre-existing forms of gender-based violence especially needs to be taken into account when reporting on sexual violence in specific conflicts and on post-conflict developments. “What is quietly emerging, but long known among humanitarian aid organizations,” The Lancet warned, “is that alongside conflict-related rape, violence by intimate partners is also highly prevalent and is likely to continue long after peace agreements have been signed.”25

A standard-setting guide for journalists on covering sexual violence in conflict zones, published in May 2021 by Dart Centre Europe, included an important section titled “Remember: Sexual violence is never the only dimension to the story.”26 It warns journalists against the “danger of getting lost in one corner of the story.”

“If you don’t provide enough focus on the wider context,” Dart’s guide clarifies, “a piece risks becoming a human-interest story ... that lacks any real purpose and offers audiences little understanding of what is happening or where solutions might lie ... . Failure to bring in wider contexts can impoverish your reporting, push away audiences and marginalize survivors.”

“REPORTING ON SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN CONFLICT”

Excerpts from Dart Centre Europe’s 2021 guidelines (sections 1 and 7)

“Before setting out, make sure you research the following dimensions:

- “What conflict-related sexual violence is and how rape and other forms of sexual violence impact individuals and their communities

- “The power politics and broader security picture in the local area, gender dynamics and cultural attitudes about sexual violence . . .

- “The cultural and religious context – including local attitudes to conflict-related sexual violence, gender-based discrimination and power imbalances within families . . .

- “Local laws in the area and any implications disclosures may have for the safety of sources and their ability to seek further judicial redress”

“Be sure to broaden the story in the following ways:

- Be careful not to predict ruination or to reduce people to the worst things that happen to them. . . . However bleak things look, it is inaccurate and prejudicial to imply that recovery is impossible.”

- “Consider that there may be other crimes beyond rape. Survivors may lose loved ones and their homes and be forcibly displaced. . . .”

- “Help your audience see paths to potential solutions by doing justice to the full political and social context.”

However bleak things look, it is inaccurate and prejudicial to imply that recovery is impossible

The Dart Center’s guidelines directly apply to some of the lessons learned in the context of both the 2014 Yazidi genocide and its aftermath, and the South Sudan civil war, which had started the year before.

In her analysis of the 2014-19 “UK newspapers’ portrayals of Yazidi Women’s Experiences of Violence under ISIS,”27 researcher Busra Nisa Sarac concluded: “The extent to which these women are the victims of violence is more highly emphasized compared to the ways they have resisted and overcome this violence. This kind of portrayal then avoids our seeing the whole story that includes women’s resistance and agency.” Instead, reporting on coping mechanisms and activism initiatives, for example, provides a fuller, more nuanced portrayal.

Sarac singled out British journalist Cathy Otten’s reporting. In a thoughtful follow-up piece in The Guardian (July 2017),28 Otten acknowledged: “It was only much later in my reporting on how some Yazidi women managed to escape and return that I became aware of how important stories of captivity and resistance were to dealing with trauma.”

Otten, who reported from Iraqi Kurdistan for four years, gave a remarkable account of her experience covering ISIS’ attacks on the Yazidi population, including the mass rapes targeting women, in a book titled With Ash on Their Faces. In her introduction, she reflected on some of the often unspoken challenges of reporting in complex and overwhelming conflict and post-conflict settings.

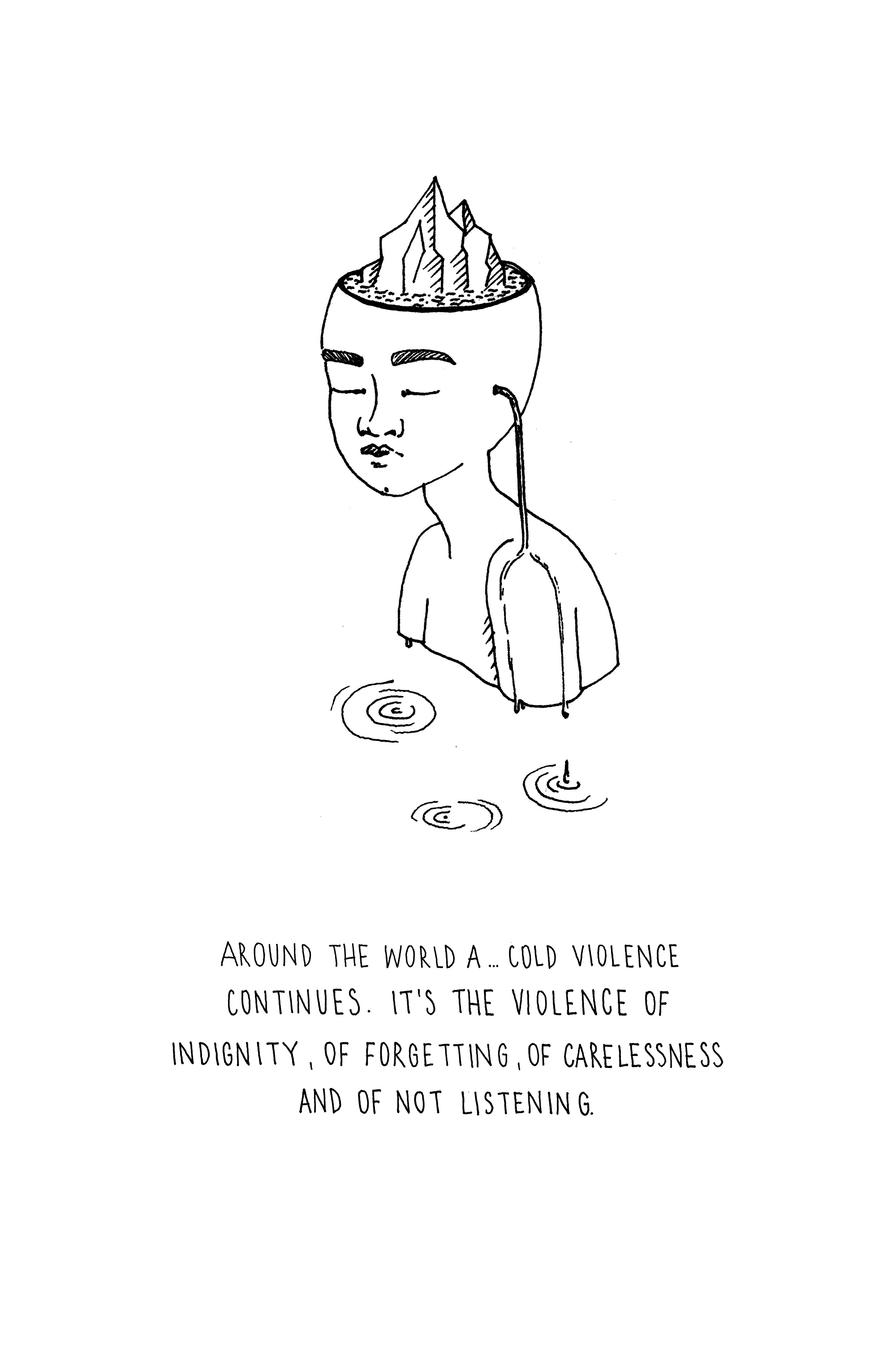

“THE VIOLENCE OF INDIGNITY, OF FORGETTING AND OF CARELESSNESS”

Excerpts from the introduction to With Ash on Their Faces by Cathy Otten (Fingerprint Publishing, India, 2017), reprinted with the author’s permission (May 2021).

"Around the world, a broader kind of cold violence continues. It's the violence of indignity, of forgetting, of carelessness and of not listening. It's there in the way politicians talk about refugees, and in the way the stateless are sometimes written about and photographed by the western media. It's there in the way humans dismiss other humans as less worthy of protection or care. When cold violence and hot violence merge, we get the "perfect storm" of genocide, of mass killings inflicted on the most vulnerable. . . .

"Yezidis have suffered massacres and oppression for generations. But there was something different about the ISIS attack that took place in the late summer of 2014. This time the western media took notice. [....] The Yezidis became the embodiment of embattled, exotic minorities against the evil of ISIS. This narrative has stereotyped Yezidi women as solely passive victims of mass rape at the hands of perpetrators presented as the embodiment of pure evil. While rightly condemning the crimes, this telling doesn't leave room for the context and history from which the violence emerged. . . .

"Though this book engages extensively with the history of storytelling as a means of promoting survival and resistance in the face of captivity, it does so without claiming that the practice is always successful. The telling of individual stories can seem to offer redemption, but it can also work to hide ongoing political failures that prevent redress and renewal and can even lead to further violence."

Researcher Carolina Marques de Mesquita, referring to analyses of the U.S. coverage of South Sudan’s civil war (including her own in 2016)29 and pointing at the unidimensional representation of women survivors, mentioned some of the issues that most media reports did not address, such as women’s own response to the violence, and the other challenges they may face during and after the conflict.

“Within the United States, South Sudan women are often presented exclusively as victims of gang rapes and other forms of sexual violence, Marques de Mesquita concluded. “Further, media give little opportunity for these women to speak about events firsthand – journalists and aid workers often speak on their behalf.”30

4.4.4.Follow-up in post-conflict settings

The impact of sexual violence often manifests itself most acutely in post-conflict settings when:

- The sexual violence escalates

- The crimes committed are not investigated and perpetrators go unpunished

- Survivors are internally displaced, forced to become refugees or stateless

- Survivors are stigmatized and rejected by their own communities or families

- Children are born of rape

- Targeted minorities are further marginalized

- Survivors are threatened for their activism against impunity, as well as redress and peace efforts

- Survivors have limited or no access to resources and services

- Media attention has waned

“All forms of gender-based violence, in particular sexual violence, escalate in the post-conflict settings,”31 The UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women Committee emphasized in its general recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict and post-conflict situations. Using Sierra Leone as a case in point, OpenDemocracy reported on the work of Women’s Forum, Sierra Leone. Its lead researcher, Rosaline Mcarthy, concluded:

“What we have found in this work is a shift from conflict-related sexual violence as a tool of war during active combat to broader and more entrenched issues like poor relationships between armed forces, former rebels and civilians; breakdown of law and order; and post-traumatic stress dis-

order experienced by victims. Poverty and social exclusion are also serious problems experienced by survivors, and these can lead to further vulnerability to violence. These are all factors that contribute to a continuum of violence from war to peace time: although fighting has ended, violence, suffering, and social chal- lenges continue.”32

Although fighting has ended, violence, suffering, and social challenges continue

4.4.4.2.Reporting on impunity and the quest for justice

Reporting on crimes of sexual violence needs to be followed by post-conflict reporting on transitional justice initiatives and mechanisms. Both the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence43 and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights have underscored and documented the importance, as well as challenges, of transitional justice. In her 2014 report to the Human Rights Council, High Commissioner Navi Pillay stated:

“Addressing gender-based and sexual violence in societies transitioning from conflict or repressive rule is vital to ensuring accountability and sustainable peace. Transitional justice processes can help to realize the rights of victims of such violence and can be instrumental in identifying and dismantling the underlying structural discrimination that enabled it to occur.”44

The following situations are meant to give journalists examples of best practices in reporting on the aftermath of conflicts, such as the fight against impunity as a main obstacle to the elimination of sexual violence. They were also selected to illustrate the key role that journalists can play in writing against forgetting.

Sexual violence under the Khmer Rouge (Cambodia)

“The Sexual Abuse of Cambodia’s History Is No Longer Invisible” (June 23, 2015)

As the global women’s rights correspondent for BuzzFeed, Jina Moore reported on the decades-long silence surrounding those crimes, even once a special tribunal, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, was set up. “The legal investigators,” Moore wrote, “like so many historians before them, largely missed one of the most common crimes of the Khmer Rouge: sexual violence.” One of the main reasons was that “the real crime [of rape] was buried by bureaucratic language as ‘organized marriage.’ ”

Waiting for justice in the Balkans

“They cannot forget. Neither should we.” (Sept. 12, 2017) https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/9/12/they-cannot-forget-neither-should-we/

In this Al Jazeera opinion piece, Amnesty International’s Balkans researcher Jelena Sesar wrote about the plight of the thousands of Bosnian women who survived the “rape camps” during the 1992-95 war, but are still denied justice and reparation. The suffering of many of the victims endured as a result of, among others, stigmatization, guilt, unemployment and poverty, psychological trauma, poor health, and lack of legal support. And it is further compounded, Sesar wrote, because “most survivors will not live long enough to see justice being done.” A survivor that she quoted said:

“The apology is important to us. It shows us society recognizes we were not responsible for what happened to us and the guilt lies elsewhere. When I watched one of the convicted war criminals admit his guilt and break down in court, saying he was genuinely sorry for all he did, I was deeply moved. I forgive him a little.”

The apology is important to us. It shows us society recognizes we were not responsible for what happened to us

“Kosovo’s attempt to help wartime rape survivors reopens old wounds” (May 10, 2018)

This Christian Science Monitor article shows the complexity of issues linked to some governments’ efforts to provide recognition and restitution to survivors. Two decades after the 1998-99 conflict in Kosovo, the government finally adopted legislation providing compensation for rape survivors. Journalist Kristen Chick, however, reported on the resulting challenges for protecting the anonymity of survivors and the “unrealistic levels of documentation” requested from applicants.

Sexual violence and impunity in Colombia

“Colombian reporter Jineth Bedoya Lima gives voice to abused women” (Dec. 14, 2013)

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/14/jineth-bedoya-lima-colombia-women

“It opens a window of hope: case will potentially set precedent for sexual violence survivors in Colombia” (March 15, 2021)

The Guardian, in several follow-up articles, has reported on sexual violence in warfare in Colombia, weaving in a compelling manner the evolution and aftermath of that protracted conflict with the story of journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima. Now Deputy Editor of El Tiempo, she has both covered the abduction, torture, and rape of women and, in 2000, suffered the same at the hands of paramilitary fighters after interviewing a detained militia leader. In the 2013 Guardian article, Bedoya Lima specified:

“In Colombia, the levels of impunity for crimes of sexual violence have reached 98%. Of the 150,000 rapes of women that had been recognized by the paramilitary groups, only 2% have resulted in guilty verdicts.”

The Guardian’s March 2021 article was published on the day of Bedoya Lima’s testimony before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. It quoted Jonathan Bock, the executive director of Colombia’s Press Freedom Foundation (FLIP), one of the organizations providing legal representation:

“This case is incredibly important as it provides the opportunity to set a precedent for the region on sexual violence carried out against journalists under the banner of armed conflict. Sexual violence against women was one of the great atrocities of the conflict and Jineth has come to represent hundreds of survivors.”

In a June 2021 update for the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas,45 Bock also emphasized Bedoya Lima’s revictimization through the frequent retelling of her story, including during the March Inter-American Court hearings, the Court ruled that Colombia is responsible for her abduction and torture and ordered a series of remedies to protect women journalists.

JINETH BEDOYA’S STATEMENT

Jineth Bedoya Lima prepared the following remarks to be presented in March 2020 for CWGL’s “Global Dialogue” on ending GBV in the world of work, which was canceled due to the pandemic. Translation by Marilse Rodríguez-García.

Today I can bear witness to what it is like to die time and again during 20 years of impunity. Today I know that I have to come alive time and again, in the midst of indifference, oblivion, and being victimized anew, because being a woman has led me to confront targeting, discrimination, and of course, having to bear the blame.

Today I can bear witness to what it is like to die time and again

Now I am fully aware that I am part of a scandalous statistic: More than two million women raped during the Colombian armed conflict because they were women, and one of thousands who face harassment and abuse while doing their job.

The Office of the Attorney General, the Colombian entity responsible for investigating and prosecuting crimes, took 11 years to ask the basic questions to establish the crime committed against me and still has not delivered the results of my claim.

It wasn't until 2016 that the paramilitary I had never been able to interview acknowledged his responsibility for the crimes committed against me; he was identified as one of the actual perpetrators. But this man owes me and Colombia the rest of the truth.

There has been no investigation of the generals of the Police and the Army who were implicated in my journalistic investigations and who would have benefitted from silencing me.

I decided the week after I was freed that the best way to end the pain was through suicide. But I lacked the courage to do it, or perhaps my love for my work got the best of me, because journalism gave me a second chance to live.

These have been very difficult years, with deep depressions, serious health problems, and a second suicide attempt. Despite that, I never, never wanted to stop working in journalism, and by my efforts I earned a position at the newspaper El Tiempo, the most important in Colombia. Today I am its Deputy Editor.

Almost 20 years after the crime that was perpetrated against me, I still have to work with a security scheme (seven bodyguards) constantly protecting me. I have to travel in an armored car and, to be able to do my work as a reporter, I often have to hide from my bodyguards in order to protect my sources.

On May 25, 2000, they silenced me. The investigation I worked on for so many years was interrupted by what happened to me that day. To date, I have not been able to publish it. But perhaps it is time to do so, despite the risk. I don't have anything to lose. On the contrary, these years of struggling to claim my rights and those of millions of women allowed me to take my case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2010. And, toward the end of 2019, the Inter-American Court accepted my complaint.

For the first time, the Colombian State will be judged before an international tribunal for the crime of sexual violence. I believe that this is why I am still alive; because my case is one of millions, but to obtain a sentence for this crime will set a precedent not only for Colombia, but for the hemisphere.

On Sept. 9, 2009, I decided to speak publicly about my rape. That was the day the campaign "No Es Hora De Callar" – Now Is Not the Time to Remain Silent - was born. With that I began my work of calling attention to and compiling cases of sexual violence, abuse and harassment, and training dozens of journalists in Colombia and Latin America on how to report about gender-based violence.

Raising my voice made possible that, by presidential decree, the anniversary of my kidnapping (May 25) was declared the National Day to Commemorate Victims of Sexual Violence. And today I belong to the Gender Parity Initiative being established by the Colombian state, to work toward equity in the workplace, as well as to stop and punish harassment and abuse.

There is much to be done. Certainly, some other day the depression will return because it is difficult to turn the page when impunity lives with you.

4.4.4.3.Survivors’ agency and solutions stories

When reporting on sexual violence in conflict, the media, understandably, tend to focus on the atrocities that victims endure and on the scope of the devastation caused by this weapon of war. Survivors, however, as well as human rights and humanitarian workers, keep stressing how crucial it is to also write about their role in rebuilding communities, seeking judicial redress, and advocating for peace.

Following are some examples of media coverage that describe their quest for solutions and successfully portray survivors as women rights’ defenders, organizers, and agents of change.

SEMA, the Global Network of Victims and Survivors to End Wartime Sexual Violence

‘Impunity reigns’: six survivors of sexual violence speak out (June 24, 2019) https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jun/24/impunity-reigns-six-survivors-of-sexual-violence-speak-out

The network was founded in 2019 as an initiative of the Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation. Dr. Mukwege, a Congolese gynecologist and women’s rights advocate, shared the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize with Yazidi survivor Nadia Murad. The network, among other services, provides a model of care for the legal and psycho-social support of survivors and advocates for concrete solutions in addressing wartime sexual violence.

One of the SEMA members (“sema” means “speaking out” in Swahili) featured by The Guardian, is Carmen Zape Paja, from the indigenous Nasa community, who was raped by FARC rebels in Colombia. She is using traditional tools to protect the rights of indigenous women targeted by wartime sexual violence.

Organizing against post-conflict gender-based violence in Colombia

“The Invisible Army of Women Fighting Sexual Violence in Colombia” (Oct. 24, 2016)

https://www.cosmopolitan.com/politics/a5278013/domestic-violence-sexual-abuse-colombia/

This thorough piece of solution journalism,46 set in the Afro-Colombian port city of Buenaventura, described the different ways that women organize to cope with and mitigate the impact of wartime sexual violence, its normalization, and challenges faced by survivors who attempt to report it.

Mobile courts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

“DRC: mobile courts deliver justice to remote areas” (Sept. 26, 2016)

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/9/26/drc-mobile-courts-deliver-justice-to-remote-areas

This Al Jazeera article47 looked at the mobile courts system set up to hear the cases of survivors of sexual violence in isolated areas, such as the small city of Bunia, in the eastern DRC. It also reports on the role of NGOs who both support the courts and challenge their effectiveness in fighting the impunity that prevents the reduction of conflict-related sexual violence.

Media houses interested in solutions-oriented reporting can disseminate relevant recommendations to governments included in the UN documents that are mentioned in the Background information at the start of this chapter.

4.4.4.4.Case study: bringing justice through media attention

American journalist Lauren Wolfe was the founder of the Women Under Siege Project of the Washington, D. C.-based Women’s Media Center. The project site publishes investigations from around the world into conflict-related sexual violence.

THE VILLAGE THAT COULD NOT SLEEP

Excerpted from Lauren Wolfe’s account, which was published by the Center for Journalism Ethics (2016)

“Unknown men in an impoverished village of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo were kidnapping dozens of girls at night, gang-raping them, and leaving them in a desiccated cassava field. Aged 18 months to 11 years old, the girls were “destroyed,” they told me. For two years, I’d been the only Western journalist reporting on these rapes – which allegedly involved sorcery – when I realized that international media attention might bring justice to this village. I went to DRC to do a long-form story for The Guardian.

I realized that international media attention might bring justice to this village

After days of immersive reporting, I identified the alleged perpetrator, which no one had seemed to be able to do in all that time. The man was a member of parliament running a kind of makeshift militia. I confirmed that an investigator, with whom I began an intense journalist-source relationship – had also identified the same suspect. He and I were the only ones who knew, he said. I consequently agreed with him that I would not reveal anything publicly until arrests were made. They would be imminent, he said.

Five months later, no arrests had been made and four more girls had been raped. I began to grapple with the hardest decision of my career: How could I publish a story that might do anything to stop this horrifying violence? Sharing too much information or publishing at all could bring harm not only to the investigation itself but to the families being victimized. Do I wait until arrests are made, despite the fact that there has been no move toward making them in nearly three years? I made a decision finally. The results were immediate. . . .”

“[The Guardian] op-ed went up on June 20. Four hours later, suddenly, the warrants to arrest the MP and 67 of his men were issued. Twelve hours later the men were all in custody. The investigator emailed me to say: ‘We have made the arrests. You can go ahead and publish everything now.’

In my nearly 20 years as a reporter and editor, I have always had a solid belief that our work can and must highlight suffering, injustice, and under-told stories. What happened in this small village in DRC reaffirmed that journalism done exactingly and without fear can create change for the public good. I began the process of reworking my long-form piece to reveal all without identifying my central source, as I’d learned my connection to him was already bringing him threats from his superiors, who did not want him to get (much deserved) credit for the arrests.

In August, my long-form story went out in the print edition of the newspaper. I protected the identity of my local sources, and allowed the voices of the survivors to be heard around the world. Not a single girl in Kavumu has been abducted or raped since.”

4.4.5.Resources

4.4.5.1.Background (reports and websites)

Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED)

ACLED is a U.S.-based disaggregated data collection, analysis, and global crisis mapping project. See the 2019 key data points and high-risk areas on sexual violence in conflict:

‘I don’t know if they realized I was a person’: Rape and sexual violence in the conflict in Tigray, Ethiopia

Amnesty International (August 2021) 39 pages

https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr25/4569/2021/en/

The State of Conflict and Violence in Asia

Asia Foundation (September 2017)

https://asiafoundation.org/publication/state-conflict-violence-asia/

The book includes a chapter, “Conflict in Asia and the Role of Gender-Based Violence,” which was written by Jacqui True, Director of Monash University Center for Gender, Peace, and Security, in Melbourne, Australia. (pp. 230-239)

“Sexual violence in armed conflicts: A violation of international humanitarian law and human rights law”

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 96 (894), 503-538. Also available in Arabic, Chinese, French, Russian, and Spanish.

Author Gloria Gaggioli, former Thematic Legal Adviser at the International Committee of the Red Cross, is the Director of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights.

Justice Without Frontiers

This NGO, based in Beirut, Lebanon, works toward the advancement of international criminal justice and promotes the rights of women who are victims of sexual violence in conflict. Attorney Brigitte Chelebian is the founder and director of the organization.

“Conflict Zones and COVID-19’s Impact on Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Reporting”

Monash University (Melbourne, Australia). December 2020.

By Jacquie True, and co-authored with Sarah E. Davies, Phyu Phyu Oo, and Yolanda Rivereros-Morales.

Mukwege Foundation

https://www.mukwegefoundation.org

International human rights organization working with survivors of conflict-related sexual violence. It is based in The Hague. Dr. Denis Mukwege of the Democratic Republic of Congo, was a 2018 Laureate of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Nadia’s Initiative

https://www.nadiasinitiative.org

Founded by Nadia Murad who shared the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize with Dr. Mukwege. She is a leading advocate for survivors of genocide and sexual violence. The organization, headquartered in Washington, D.C., advocates globally for survivors of sexual violence, while focusing on rebuilding Yazidi communities. It is a key consultant in the development of the draft Murad Code (see below).

The Oxford Handbook on Atrocity Crimes

Oxford University Press (January 2022) 984 pages

Includes a chapter by Kim Thuy Seelinger and Elisabeth Wood on Sexual Violence as a Practice of War: Implications for the Investigation and Prosecution of Atrocity Crimes.

SEMA Network

SEMA is a global network of victims and survivors to end wartime sexual violence and impunity, headquartered in The Hague.

Synergy for Justice

https://www.synergyforjustice.org

London-based, women-led justice organization working globally to advance accountability for torture and sexual violence.

See especially:

Knowledge, Attitudes and Stigma Surrounding Sexual Violence in Syrian Communities

(April 2021)

Principles for Global Action: Preventing and Addressing Stigma Associated with Conflicted-Related Sexual Violence

Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (UK Foreign Office), September 2017

Trial International

https://trialinternational.org

This Geneva-based international NGO fights impunity for international crimes and publishes annual reports on the prosecution of sexual violence:

https://trialinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Unforgotten_2019.pdf

We Are Not Weapons of War (WWoW)

http://www.notaweaponofwar.org

Available in Arabic, English, French and Spanish

The organization’s founder and president, Céline Bardet, is an international jurist specializing in in war crimes. WWoW fights impunity against rape as a war crime.

Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice

Based in The Hague, this international women’s human rights organization advocates for gender justice through the International Criminal Court as well as domestic courts and mechanisms. Its 2019 consultation with survivors of sexual violence and civil society led to the development of

The Hague Principles on Sexual Violence

https://4genderjustice.org/ftp-files/publications/The-Hague-Principles-on-Sexual-Violence.pdf

Available in Arabic, English, French, Georgian, Russian and Spanish

This set of three documents includes The Civil Society Declaration on Sexual Violence which “provides guidance on what makes violence ‘sexual’, especially to survivors.”

UNFPA Regional Syria Response Hub

The regional hub, based in Amman, Jordan, publishes monthly Regional Situation Reports for the Syria Crisis, which regularly include information about the humanitarian impact of the conflict and its gender dimensions.

United Nations

https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/sg-reports/

Each April, the Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict releases the UN Secretary-General’s report on this issue.

4.4.5.2.Relevant handbooks and media guidelines

Reporting on Sexual Violence in Conflict

Dart Centre Europe (May 2021). Available in Arabic, English, French, Spanish and Swahili

https://dartcenter.org/resources/reporting-sexual-violence-conflict

A set of comprehensive guidelines “designed for deeper learning, quick reference and easy sharing with colleagues.” Aimed at promoting contextual reporting and a better understanding of the impact of trauma, these thoughtful guidelines focus on interviewing best practices that respect the dignity and voice of survivors.

“Visual choices: Covering sexual violence in conflict zones”

by Nina Berman (May 13, 2021)

Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma (Columbia Journalism School, New York)

https://dartcenter.org/resources/visual-choices-covering-sexual-violence-conflict-zones

Towards Ethical Testimonies of Sexual Violence During Conflict

by Nayanika Mookherjee and Najmunnahar Keya (2018). Available in Bangla and English.

https://www.ethical-testimonies-svc.org.uk/

This unique set includes guidelines for journalists and researchers documenting wartime rape, a graphic novel, and an animated film. It is based on research by Mookherjee (Professor in the Anthropology Department at Durham University, UK) on the 1971 war that led to the formation of Bangladesh and resulted in the rape of 200,000 women by the Pakistani army. Interviews with survivors led to the development of those guidelines for ethical reporting and documentation.

IICI Guidelines on Remote Interviewing

Institute for International Criminal Investigations (August 2021) 14 pages

https://iici.global/0.5.1/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/IICI-Remote-Interview-Guidelines.pdf

These guidelines were drafted to help conduct remote interviews mostly in the context of investigations into grave human rights violations in conflict-affected areas. Although prepared for investigators and researchers working for international entities such as UN agencies, NGOs and commissions of inquiry, the guidelines can also be very useful to media professionals.

Reporting for Change: A Handbook for Local Journalists in Crisis Areas

Institute for War and Peace Reporting (2004)

Available in Arabic, English, Farsi, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, and Russian

Geographic focus is Central Asia.

Murad Code

https://www.muradcode.com/draft-murad-code

This Draft Global Code of Conduct for Investigating and Documenting Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (named after Yazidi advocate Nadia Murad) is the result of a remarkable interdisciplinary collaboration between Nadia’s Initiative, the UK government’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), and the Institute for International Criminal Investigations. The Code is being drafted for organizations and individuals, such as journalists, investigators, researchers, and interpreters, who work in direct contact with survivors.

Conflict-Sensitive Coverage: A Manual for Journalists Reporting Conflict in West Africa

Edited by Audrey S. Gadzekpo (2017)

School of Information and Communication Studies, University of Ghana, Legon

Includes a chapter on “Media coverage on gender during conflict and peacebuilding” by Peace Adzo Medie.

Guidelines for Gender and Conflict-Sensitive Reporting

UN Women Europe and Central Asia (2019). Available in English and Ukrainian.

Reporting on Violence Against Women and Girls

by Anne-Marie Impe

UNESCO publication (2020) 153 pages

Available in Arabic, English, French, Kirghiz, Russian and Spanish

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371524

Includes a section (1.9.) on Violence against women in conflicts (pp.82-93)

4.4.6.Endnotes

Endnotes of Chapter 4:

- United Nations, Security Council, Conflict-related sexual violence: report of the Secretary-General, S/2021/312 (30 March, 2021), par. 5. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/sg-reports/

- Rehn, E. and Johnson Sirleaf, E. (2002). Women, War, Peace: The Independent Experts’ assessment of the impact of armed conflict on women (Progress of the World’s Women, 2002, Vol.1). UN Women. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2002/1/women-war-peace-the-independent-experts-assessment-on-the-impact-of-armed-conflict-on-women-and-women-s-role-in-peace-building-progress-of-the-world-s-women-2002-vol-1

- Arradon, I. (2018, March 7). A hidden face of war. International Crisis Group. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/hidden-face-war

- United Nations, Human Rights Council, Sexual and gender-based violence in Myanmar and the gendered impact of its ethnic conflicts. A/HRC/42/CRP.4 (22 August, 2019). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/FFM-Myanmar/sexualviolence/A_HRC_CRP_4.pdf

- UN Security Council resolution 2467, S/RES/2467 (23 April 2019). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://undocs.org/S/RES/2467(2019)

- Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (2019, April 29). Press release. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/press-release/landmark-un-security-council-resolution-2467-2019-strengthens-justice-and-accountability-and-calls-for-a-survivor-centered-approach-in-the-prevention-and-response-to-conflict-related-sexual-violence/

- Ford, E. (2019, April 23). UN waters down rape resolution to appease U.S.’ hardline abortion stance. The Guardian. Retrieved on July 31, 2021 from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/apr/23/un-resolution-passes-trump-us-veto-threat-abortion-language-removed

- International Criminal Court (1998, July 17). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.icc-cpi.int/resource-library/documents/rs-eng.pdf

- International Committee of the Red Cross. The Geneva Conventions of 1949. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/war-and-law/treaties-customary-law/geneva-conventions/overview-geneva-conventions.htm

- Prosecutor’s Office of the International Criminal Court (2014). Policy paper on sexual and gender-based crimes. https://www.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/otp/otp-policy-paper-on-sexual-and-gender-based-crimes--june-2014.pdf

- Ibid. See Executive summary sections 3-5 and 11.

- Burke, J. (2021, May 6). ICC sentences Ugandan Lord’s Resistance Army leader to 25 years. The Guardian. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/law/2021/may/06/icc-sentences-ugandan-lords-resistance-army-leader-dominic-ongwen-to-25-years

- International Criminal Court (2017, June 15). Ntaganda case: ICC Appeals Chamber confirms the Court’s jurisdiction over two war crime counts. ICC press release. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=pr1313

- Inder, B. (2017, December 7). Farewell Speech (New York). Brigid Inder, OBE gave this speech before leaving her post as executive director of Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://4genderjustice.org/uncategorized/farewell-executive-director/

- Brown, D. (2021, June 18). Accountability for sexual and gender-based crimes at the ICC: An analysis of Prosecutor Bensouda’s legacy. International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Women’s Initiatives for Gender Justice. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/cpiproc772ang-1.pdf

- Hutchinson, S. (2019, Nov. 25). Rape prosecution must drive the new Rohingya genocide court case. PassBlue. Retrieved on July 31. 2021, from https://www.passblue.com/2019/11/25/rape-prosecution-must-drive-the-new-rohingya-genocide-court-case/

- Moyn, S. Human Rights And The Uses Of History. (Verso 2017).

- Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (2020. July 17). Sexual violence shreds ‘very fabric that binds communities together’, Special Representative tells Security Council, stressing survivor-centered approach. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/sc14257.doc.htm

- Nichols, M. (2021, May 10). UN investigator says he has evidence of genocide against Iraq’s Yazidis. Reuters. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-investigator-says-evidence-genocide-against-yazidis-iraq-2021-05-10/

- United Nations, Security Council, Conflict-related sexual violence: report of the Secretary-General, S/2021/312 (30 March, 2021), par. 5. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/sg-reports/

- United Nations, General Assembly, Rape a grave, systematic and widespread human rights violation, a crime and a manifestation of gender-based violence against women and girls, and its prevention: report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, A/HRC/47/26 (19 April 2021), par. 60. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://undocs.org/A/HRC/47/26

- Crossette, B. (2021, April 12). Russia, the current big spoiler in advancing global gender rights. PassBlue. Retrieved on July 31,2021, from https://www.passblue.com/2021/04/12/russia-the-current-big-spoiler-in-advancing-global-gender-rights/

- United Nations LGBTI Core Group (2021, April 14). Open Debate “Sexual violence in conflict: statement of LGBTI UN Core Group. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://unlgbticoregroup.org/2021/04/14/sexual-violence-in-conflict/

- Maloney, M. (2020, November 25). Sexual violence in armed conflict: can we prevent a COVID-19 backslide? International Committee of the Red Cross blog. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2020/11/25/sexual-violence-covid-19-backslide/ https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/beyond-helpless-victim/6

- The Lancet (2014, June 14). Preventing violence against women and girls in conflict. The Lancet, Vol. 383. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60964-8/fulltext

- Dart Center Europe (2021, May 27). Reporting on Sexual violence in conflict (section 7). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://dartcenter.org/resources/reporting-sexual-violence-conflict

- Sarac, B.N. UK Newspapers’ portrayal of Yazidi women’s experiences of violence under Isis. Journal of Strategic Security 13, no. 1 (2020): 59-81. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1753&context=jss

- Otten, C. (2017, July 25). Slaves of Isis: the long walk of the Yazidi women. The Guardian. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/25/slaves-of-isis-the-long-walk-of-the-yazidi-women

- Marques de Mesquita, C. (2016, December 8). Beyond the helpless victim: Media representation of women in conflict zones. New America Weekly. Retrieved on August 3, 2021, from https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/beyond-helpless-victim/

- Marques de Mesquita, C. (2017, March 23). Telling the whole story of South Sudan’s civil war. New America Weekly (www.newamerica.org). Retrieved on August 3, 2021, from https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/telling-whole-story-south-sudans-civil-war/

- United Nations, CEDAW Committee, General recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict and post-conflict situations, CEDAW/C/GC/30 (18 October 2013). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://undocs.org/CEDAW/C/GC/30

- Mcarthy, R. (2019, July 3). Links between conflict-related violence and peace time practices: perspectives from Sierra Leone. openDemocracy. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/links-between-conflict-related-violence-and-peace-time-practices-perspectives-sierra-leone/

- Care International (2021, January 11). The 10 most under-reported humanitarian crises of 2020. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.care-international.org/news/press-releases/new-care-report-the-10-most-under-reported-humanitarian-crises-of-2020

- United Nations, Security Council, Conflict-related sexual violence: report of the Secretary-General, S/2021/312 (30 March, 2021). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/reports/sg-reports/

- Ibid.

- Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (2021, January 21). UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Ms. Pramila Patten, urges all parties to prohibit the use of sexual violence and cease hostilities in the Tigray region of Ethiopia. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/press-release/united-nations-special-representative-of-the-secretary-general-on-sexual-violence-in-conflict-ms-pramila-patten-urges-all-parties-to-prohibit-the-use-of-sexual-violence-and-cease-hostilities-in-the/

- Kassa, L. (2021, February 11). A rape survivor’s story emerges from a remote African war. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-02-11/troops-accused-of-mass-rape-in-ethiopias-tigray-conflict

- Kassa, L. (2021, February 11). I reported on Ethiopia’s secretive war. Then came a knock at my door. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-02-11/i-reported-on-ethiopias-secretive-war-then-came-a-knock-at-my-door

- Kassa, L. (2021, June 29). Death threats and sleepless nights: The emotional toll of reporting Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict. The New Humani- tarian. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https:// www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/ first-person/2021/6/29/emotional-toll-of-reporting-ethiopias-tigray-conflict

- Castañeda Camey, I., Sabater, L., Owren, C., & Boyer, E. (2020). Gender-based violence and environmental linkages: The violence of inequality. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/48969

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (2018, March 8). Indigenous women target of rape in land-related conflicts in Bangladesh. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://www.iwgia.org/en/bangladesh/3235-indigenous-women-target-of-rape-in-land-related-conflicts-in-bangladesh.html

- Csevár, S. and Tremblay, C. Sexualized violence and land grabbing: Forgotten conflict and ignored victims in West Papua. London School of Economics blog. Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2019/08/21/sexualised-violence-and-land-grabbing-forgotten-conflict-and-ignored-victims-in-west-papua/

- United Nations, General Assembly, The gender perspective in transitional justice processes: report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence, Fabián Salvioli, A/75/174 (17 July 2020). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://undocs.org/A/75/174

- United Nations, General Assembly, Analytical study focusing on gender-based and sexual violence in transitional justice: a report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (par. 7), A/HRC/27/21 (30 June 2014). Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/068/34/PDF/G1406834.pdf?OpenElement

- Higuera, S. (2021, June 9). Inter-American court’s decision in Jineth Bedoya case could be transformational for Colombian journalists, says watchdog. Latin America Journalism Review (Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, University of Texas at Austin, U.S.A.) Retrieved on July 31, 2021, from https://latamjournalismreview.org/articles/inter-american-courts-decision-in-jineth-bedoya-case-could-be-transformational-for-colombian-journalists-says-watchdog/

- Written by Jean Friedman-Rudovsky when she was an Adelante Latin America Reporting Fellow with the International Women’s Media Foundation.

- Written by Katya Cengel when she was a fellow with the International Women’s Media Foundation’s African Great Lakes Reporting Initiative.